One of many things that thwart my irregular attempts at ‘cleaning up’ – apart from getting started at all – is that, inevitably, I discover something that re-piques my interest.

I start reading anew and, before I know it, it’s: “Wow, is that the time,” and the period allocated to cleaning has expired. I lose interest in cleaning up and clearing out much more quickly than I lose interest in almost any article I’ve ever set aside.

Occasionally, you unearth a gold nugget, a piece of such value that you wonder how it ever got onto the scrapheap at all. Such a moment occurred recently when I came across the transcript of a talk given by Ron Clarke.

It was 10 January, 1992, almost 27 years ago to the day, that ‘Clarkie’ gave a talk to a group of runners at Ferny Creek Recreation Reserve in the Dandenong Ranges on the outer eastern fringes of Melbourne, where he did so much of his training.

The runners were mostly members of Glenhuntly, Clarke’s old club, but leavened with healthy numbers from other clubs. The connection was as much running at Ferny as it was to any one club.

Ron’s oldest son, Marcus, lived and worked in Melbourne then, but it was a few years before Ron, Helen, Monique and Nicholas moved back to Australia for Ron to set up the Couran Cove eco-resort. He must have been on one of his regular visits.

We gathered around the picnic tables under the giant trees. The reserve sits on the corner of Sherbrooke Forest, one of several blocks of rain-forest making up the Dandenong Ranges national park.

Trevor Vincent, Ron’s old friend, training partner and clubmate, was there. So, too, was Frank McMahon, who coached Ron from 1964 through to the end of his career, and whose various houses in the Dandenongs formed the bases for the original training runs. Chris Wardlaw, mid-way along the transition from dual-Olympic distance rep to Sydney 2000 Olympic athletics head coach, was also there.

One or another of us must have had a hand in organising the session but, funnily enough, none of us can recall precisely who did. Anyway, like so many Ferny Creek training runs, we all got there and off we went.

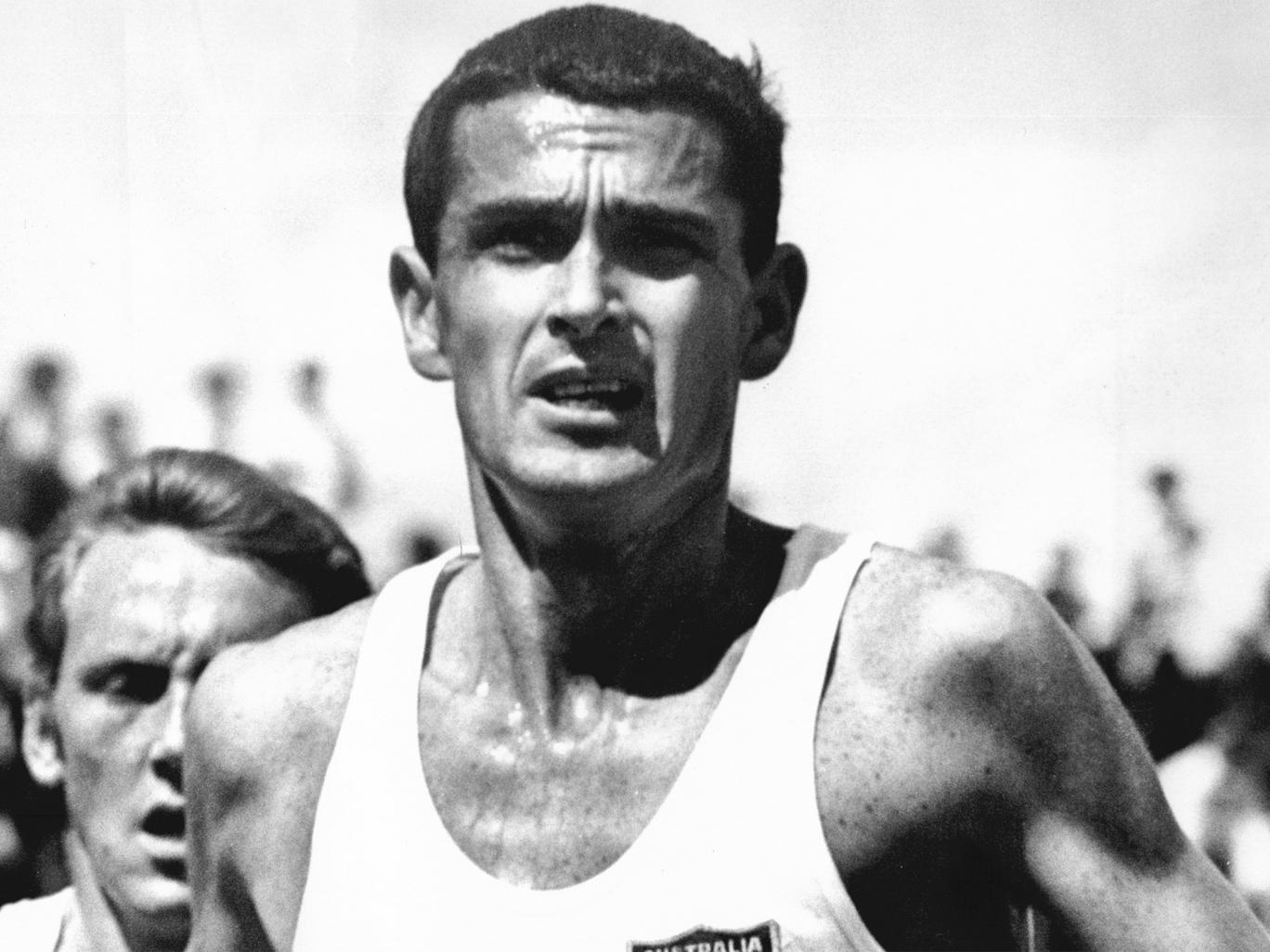

For the next hour, and more, Ron opened up about anything and everything connected with running. He ranged freely over training, coaching, administration, Olympics – all of it laced freely with personal anecdotes. Some of these illustrated the points he was making, others were entertaining diversions.

Ron was into his 50s by then, but every person listening was old enough to remember his glory days and to have been inspired by his example. We hung on every word. He began with a preamble, then took questions along the way.

“Clarkie” said that if he had a philosophy on running it would be that it is a simple activity. “Running gets over-complicated really, It’s a simple sort of sport.” Like all sports, he believed, it had its own rhythm “which you get, mainly, from simply running.”

The best form of speed work was racing, said the man who raced 50 and more times a year (plus several interclub and relay races which did not make the list). Like present-day marathoner Yuki Kawauchi, Clarke got almost all his quality work from racing. In training, his staple, and usually only, session of faster running each week was 10 laps of straights, sprinting the straights and floating round the bends.

“I found training boring if I wasn’t racing,” he told us.

Clarke wasn’t prescriptive on training – “there’s so many ways to get there it doesn’t matter.” The key, he said, was “up here” (Ferny Creek), citing the 17-miler, which warmed up with dashes along a couple of twisting creekbank tracks before climbing 2-mile hill. The group used to be competitive running up the longer hills, but it was otherwise relaxed running at talking pace.

Mondays or Tuesdays Clarke would do the 10-lapper, a session devised by Frank McMahon. After a four or five mile warm-up, it would be on to the track.

With multiple Olympic hurdles medallist Pam Kilborn and 400 metres bronze medallist Judy Pollock each running repetitions along one of the two straights, Clarke and his partners would run race rhythm around the bends and sprint flat-out along the straights.

Speaking about it on another occasion, Clarke described these sprints as “going as fast as you could, so you were getting one foot in front of the other just before you felt you were going to fall down.” Usain Bolt might not ecognise that depiction of an all-out sprint, but most of us middle and long-distance runners were familiar with the feeling.

The rest was “just Caulfield Racecourse,” said Clarke. Living not far from the racecourse, I had some personal experience. One night in the early 1970s – when Clarkie had “retired” and Derek Clayton was “considering” a comeback – the pair came past me as I was on my last lap. They were already 50 metres ahead by the time I decided to try to hold the gap at that over my last 1500 metres or so. I did, but only by dint of going pretty-well flat out. And, all the time, I could hear the conversation between the pair of them floating back to me.

Training explained, it was on to various anecdotes about Europe, including the ‘world record’ 10,000 in Turku at the start of his fabulous 1965 tour, in which Clarke spent most of race eve rowing back-and-forth from the cabin on the lake to the phone on the shore negotiating with an Australian official for permission to add the race to his schedule. In the end, he ran 28:14 to shave a second or so from his own world record, though the performance was never ratified officially.

Clarke loved racing against other runners and his observations on various opponents were incisive and illuminating. Kip Keino always gave you a chance to beat him, Michel Jazy was obsessed with knowing how the race was to be run, Gerry Lindgren just went out and took the race on. In these days of micro-managed training and racing programs, Clarke and his contemporaries showed a refreshing willingness to race each other many times a season.

On coaches, Clarke said he respected their role, but some were over-rated. He once famously said that his own grandmother could have coached Herb Elliott successfully, such was his talent; and, while he said he perhaps shouldn’t be quoted on Peter Coe, he clearly thought she could have coached Sebastian Coe, too.

Ron Clarke always raced freely, giving spectators value for money rather than running purely to win, and he gave generously of his knowledge and opinions on that long-ago January summer morning. He was always worth watching, and worth listening to as well.

I had truly unearthed a precious gold nugget.

End