Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

The road distance event at the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games will be a half-marathon, at least compared to its immediate predecessor at Rio 2016.

No, the traditional, 42.195-kilometre distance will not be slashed by 50 percent (fiddling with the distance might be grounds for revolution in marathon-obsessed Japan): the field will be.

The IAAF released the qualification system for Tokyo just recently, along with the quota numbers for each event. Almost all the event quotas remained the same: the multi-events and the marathon took a hair-cut.

The multis copped just a trim, the numbers in the heptathlon and decathlon reduced from 32 to 24. But it was the old short-back-and-sides for the marathons: there were just under 160 competitors in both the men’s and women’s events in Rio, there will be room for 80 only in Tokyo.

Admittedly, the cut seems more drastic given that Rio’s participation numbers ballooned out by almost one-third over London 2012. Nonetheless, 80 still represents a sizeable reduction from the 105 men and 118 women who competed on the streets of the British capital.

If you’ve been paying attention to Olympic matters, you will recall that the IOC moved to tighten the cap on overall participation for Tokyo 2020 at the same time as it found space for several new sports – rock climbing, skateboarding, surfing and karate, the return of baseball/softball and the addition of new events in existing sports.

Many of the new events relate to mixed competition. Swimming and athletics will have mixed relays – a mixed medley relay for the former adds the mixing of genders to the mixing of strokes, while on the track there will be a mixed 4×400 contested in addition to the existing 4x400s.

Swimming has also solved its Olympic long-distance anomaly – 800 freestyle for women versus 1500 for men – not by acknowledging that women should swim the 1500, but by letting both men and women contest both distances. Admittedly, swimming has long had both distances at its world championships, but it is ironic that even as the IOC squeezes new sports into the same overall athlete numbers, it allows new events in long-established sports.

Of course, several agendas are colliding here. The IOC is desperate to appear more ‘relevant’ to what it sees as a changing world, hence the moves to add edgier sports and events assumed to have ‘youth’ and/or media appeal (I would have said television, but increasingly it is about social media platforms!). And it is not possible to mount an argument against gender equity – not a sensible one, anyway.

This was the conundrum facing the IOC when it looked at accommodating more sports in Tokyo within the same overall numbers. Athletics’ part in the solution was to cop a cut of 105 from its total quota. Even using the London numbers in preference to Rio, it seems most of that cut will come from the marathons with a significant contribution from the multi-eventers, too.

Mind you, given the record summer swelter in Tokyo two years out from the Games, marathoners might be thinking they would have been better off had the distance been cut in half, rather than the field.

Prospective Tokyo marathoners are not the only ones trying to get their heads around likely conditions in the Japanese capital two years from now. All athletes are waiting to see how the new qualification by rankings system will play out.

One thing seems sure; all athletes will be affected. What remains to be seen is how. With the ranking score being based on an average of five performances across almost all events (less for the less-frequently contested events such as the marathon, road walks, the track distances and the multis) it is hard to envisage a system that can cope with the sometimes rapid emergence of talented athletes.

Let’s take one of Australia’s hottest events right now – the men’s 800 metres. Coming in to this year, Joseph Deng would not have had a high ranking score. Now the Commonwealth Games team is not an IAAF competition but were it to be selected under a ranking system it’s difficult to see how Deng – or Keely small in the women’s event – could have been picked.

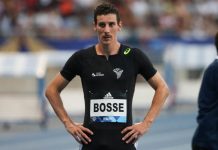

Luke Mathews, on the other hand, would have been more favoured by such a system. Then he took a bronze medal at the Games, so he would remain well placed. Since then, however, the tables have flipped: Mathews has been injured, Deng has gone from strength to strength with a national record and three more sub-1:45 performances.

Now, assume nothing else changes and Mathews retains his title next year. Presumably, he would not have raced often over 800 at that stage, so his ranking would be relatively low although Australia would dearly love to pick him. In any case, the rankings score vis-à-vis Mathews and Deng would have flipped in 12 months.

Of course, seeing it would only be March, 2019, both Deng and Mathews would have plenty of time to compete and, on their 2018 performances, compile a ranking score which would guarantee both a place in the team – but that would be based on performances outside Australia, not comparative form against other Australian athletes.

Countries which have traditionally based their teams on selection trials will face similar problems, perhaps in multiple events. One area which has been clarified, however, is that where a country has more than three athletes with a ranking that would get them a place, the national federation will nominate the three. Otherwise, national federations could be cut out of the selection process to an alarming degree.

We’re far enough advanced along the ranking system path, however, that it seems we have no other option than to wait and see how it works. The IAAF is getting feedback from national federations now. The release of the Doha 2019 qualification system is imminent. Stand by for fun, as well as Games.