About the only English people feeling less than devastated about England’s World Cup exit are the people staging England’s World Cup this weekend (14-15 July).

How’s that, you ask. Well, England lost in football’s World Cup semi-finals to Croatia and won’t be further involved, the third/fourth place playoff aside. Instead of football coming home for the first time since England won the World Cup in 1966, it will once again be English footballers coming home. We sympathise, but not too much: the Socceroos have been back home for some time now.

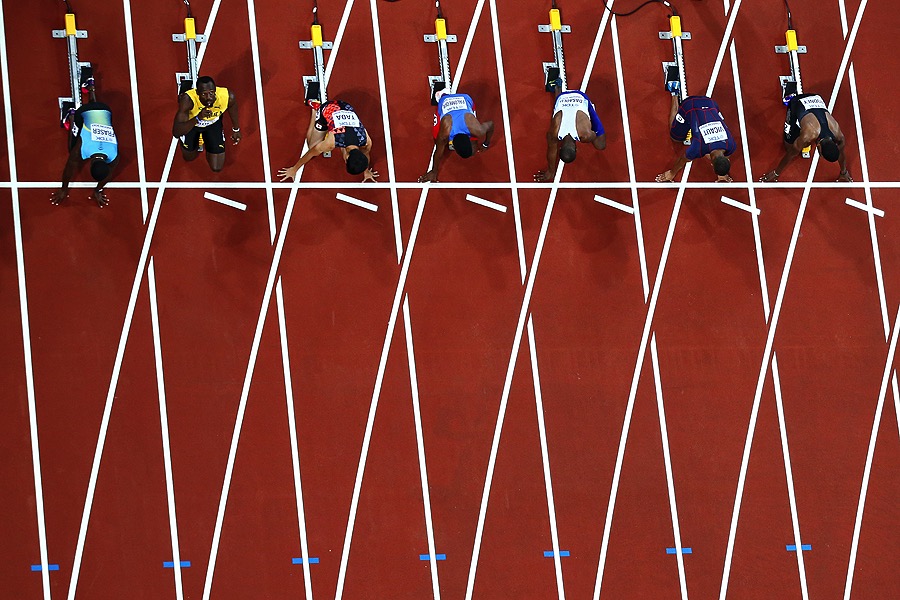

The World Cup final will still play pretty big in the UK, you’d think, despite being slightly diminished now that England won’t be part of the big one at Moscow’s Luzhniki Stadium. But it will be one less distraction from the other World Cup involving Britain/England this weekend, the Athletics World Cup at London Stadium.

To read the publicity, the wonder is that this other World Cup is being staged at all. The expected highlights are not which star athletes will be there, but the many who won’t. Picking just some names from the headlines, Noah Lyles is a ‘no’, so is Laura Muir. Zharnel Hughes won’t be there to fight out the closing stages of the 200 with whomever is in the adjoining lane; Justin Gatlin won’t be there to be booed; and, perhaps due to his record at world championships, Renaud Lavillenie is understandably shy of appearing at any event with “World” in its title.

The scarcity of big-name athletes is just one of the obstacles facing the World Cup. The timing is seemingly against it, too. July brings a logjam of major sporting events to Britain. As well as the football World Cup final, the finals at Wimbledon will be played this weekend (World Cup organisers were probably buoyed by Roger Federer’s defeat in the quarter-finals). The British Formula 1 Grand Prix was held last weekend and the British Open (golf) gets under way next Thursday.

Topping it all, the Athletics World Cup is also going up against London’s Diamond League meeting, to be held on 21-22 July, and follows one day after the DL meeting in Rabat.

Such scheduling will be a stern test of Roy and H.G.’s assertion that “too much sport is barely enough.”

Presumably, the date clashes and other problems were known when the World Cup dates were set. The more conspiratorial amongst us might even wonder whether organisers deliberately set a low bar for what they knew would be a hard-sell event. UK Athletics chief executive Niels de Vos may have been a bit disingenuous when he told The Guardian: “It’s frustrating when people look for the weak points rather than the fabulous points, but that is the nature of the world.”

Surely the fixture and event clashes, not to mention the “nature of the world”, have been “knowns” for some time.

Regardless, I sympathise with the organisers. Back in the early days of this column, I wrote of the difficulties of promoting the old World Cup (now the Continental Cup), experienced first-hand as I tried to explain the absence of Carl Lewis on Australian breakfast television, all the time standing with one shoe – the one with the hole in it! – in a puddle of water.

My role back then was as the athletics ‘expert’ on the Canberra 1985 World Cup staff, employed to engender some publicity for the event. It was no easy task, for many of the same reasons as the current World Cup.

Athletics is a sport of individuals, with minor exceptions for relays and cross-country. It lends itself to a star system. Fans, both rusted-on and more casual, look for the best performers and are more likely to mark down an event which doesn’t feature stars with broad name recognition. The absence of Carl Lewis, Usain Bolt or Sally Pearson is more of a negative than the absence of Christian Ronaldo or Lionel Messi from the semi-finals and final of the football World Cup, say.

Additionally, teams contain one, at most two, representative per event. One of the questions back in 1985 was whether Coe, Ovett and Cram were coming. No, you would explain, Europe (the team they would be representing) could have just one 1500 runner. Ultimately, it was Spain’s Jose Manual Abascal, bronze medallist behind Coe and Cram at the previous year’s LA Olympics. Didn’t matter who he was, he was not Coe, not Ovett, and not Cram.

Then there were problems of timing. Local Canberra organisers had wanted the event to be staged on 5, 6 and 7 October, taking advantage of a weekend followed by a Monday public holiday. The IAAF overrode this, largely to suit European television. It was a better decision from the international perspective, but meant the Cup got under way on a working Friday before a smaller crowd.

As already mentioned, the World Cup has been re-styled since 2010 as the Continental Cup. The teams now represent the five IAAF continental areas and there are two per team in each event. The third edition of the Continental Cup will be held in Ostrava on 8-9 September.

The World Cup label went into abeyance before being attached to the London event, based on the top eight nations from last year’s world championships. I hope the IAAF got something for the intellectual property

The attraction of team events is the score. It is difficult from this distance to see the London event being an overwhelming success, despite the ‘help’ of very low expectations. But if the Cup comes down to the last two events – the women’s 4×100 and men’s 4×400 – with several teams still in contention, it will generate its own excitement.

Canberra’s World Cup turned out to be an entertaining and moderately successful. We’ll know in a couple of days whether the London World Cup can likewise surpass the modest expectations most have of it.

Comments are closed.