By Len Johnson

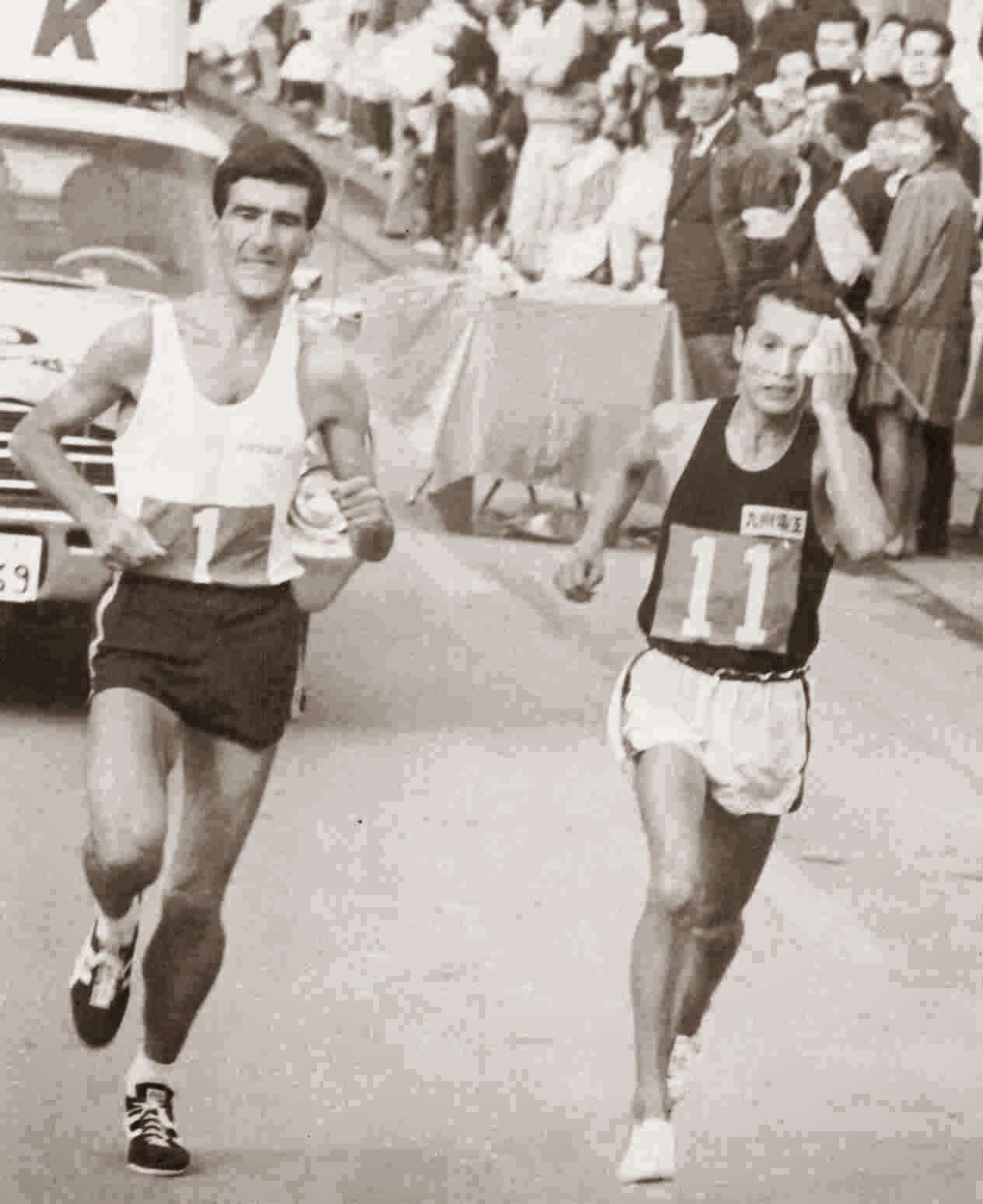

Japan’s Fukuoka marathon used to be the best non-championship marathon of the year.

You knew when it would be run: the first Sunday in December each year. You knew who would be running: the best six international runners organisers could get on a ‘start at the top and keep going until six men have said ‘yes’’ basis; the best six Japanese runners (few of whom ever said ‘no’ to Japan’s most prestigious race); anyone else around the world who had bettered the 2:27 qualifying time and was willing to pay their own way.

The Olympics were the only global championships back then, so most years Fukuoka might bring together the European and Commonwealth champions, the winners of traditional races like Boston and the English AAA championship and others burning with ambition. Before there was a world championships, the Fukuoka marathon was the next-best thing.

The essence of Fukuokas past was captured beautifully by Kenny Moore in the “Concentrate on the Chrysanthemums” chapter of his classic running book, Best Efforts. It is written around the 1971 race. Frank Shorter won his first of four straight Fukuoka marathons that year. He was little-known then, but returned as Olympic champion the following year. Moore finished fourth in the Olympic race. The legendary Jack Foster was one of four New Zealanders; Australia’s John Farrington was there, too, along with two well-credentialled Soviet runners.

Fukuoka is on again this Sunday, reduced by Covid-19 to largely domestic race status, augmented by a half-dozen Japan-based Kenyans and Ethiopians. With the fastest two Japanese last-minute withdrawals, possibly the best-known name is Bedan Karoki, who will be helping pace one of his corporate team team-mates (as well as everyone else).

Now in its seventy-fourth year as an international race, it is hard to envisage the modern Fukuoka marathon as a virtual world championships. It still has its moments – most recently when Sammy Wanjiru made his marathon debut there in 2007 and won in 2:06:39 a year before winning the gold medal at the Beijing Olympics in what many rank as the greatest marathon championship performance. In an era when fast times in bulk are the criterion for quality, Fukuoka is struggling to keep up, albeit the its tradition is still respected.

Step forward the Valencia Marathon, this weekend’s (5-6 December) other major international marathon. Valencia got started in 1981, the same year Rob de Castella set a world record 2:08:18 in winning at Fukuoka. It would be three years and four races before anyone broke 2:20, 29 years and 30 races before anyone broke 2:10. Now the race record, set last year by Ethiopia’s Kinde Atanaw, is 2:03:51. It took 22 races before a woman broke 2:30; last year another Ethiopian, Roza Dereje, won in a record 2:18:30.

Impressive, to be sure, but 2020 could see all previous records not only broken but wiped out by a veritable avalanche. A combination of Covid-induced cancellations of alternative competitions and sponsor’s pockets so deep as to make even those of races like London and Berlin shallow by comparison sees a gathering of fast marathoners in Valencia like no other in history.

Like Fukuoka in bygone years, Valencia has been targeting the best and has the wherewithal to accommodate them. That much is the same; the rest is completely different.

Our friends at LetsRun.com have been crunching the numbers. The headline figure on the men’s race is that there are nine entrants who have better 2:05, 14 sub-2:06, 23 sub-2:07, 25 sub-2:08, 35 sub-2:10 and a staggering 44 sub-2:12.

On the women’s side, the numbers to have broken 2:21 to 2:25 minute-by-minute are eight, nine, 13, 17 and 19, respectively.

LetsRun compared the Valencia 2020 figures to the previous deepest marathon entry lists since 2017:

| Deepest Marathon Ever | ||

| 2020 Valencia | Next-best major | |

| Sub-2:05 men | 9 | 8 (2015/2019 London) |

| Sub-2:06 men | 14 | 11 (2020 Tokyo) |

| Sub-2:07 men | 23 | 14 (2020 Tokyo) |

| Sub-2:08 men | 25 | 15 (2019 Boston) |

| Sub-2:21 women | 8 | 8 (2019 London) |

| Sub-2:22 women | 9 | 9 (2019 London, 2020 Tokyo) |

| Sub-2:23 women | 13 | 11 (2019 Boston) |

| Sub-2:24 women | 17 | 12 (2019 Tokyo, 2019 Boston) |

| Sub-2:25 women | 19 | 12 (2019 Tokyo, 2019 Boston, 2020 Tokyo) |

It’s a staggering array of marathon speedsters and, if the race proceeds like most modern marathons – that is, like a bike race with domestiques assigned to the pacing duties with the peloton tucking in behind – could produce an equally staggering accumulation of fast times.

Where the process in Fukuoka years ago could be implemented with an annual top performers’ list and an index of contact numbers for the various national federations, Valencia 2020 has harvested the world’s top marathoners with the efficiency of a search engine algorithm.

We will know whether that process produces a memorable race by Sunday night. The pen and paper worked pretty well for years for Fukuoka, let’s see how Valencia handles the opportunity the pandemic has laid at its start-line this year.

Like so many other things about 2020, the chance might be a once-off. As LetsRun also notes, things will be vastly different again in 2021 (presuming the world has vanquished the virus) when all six major marathons, plus the Olympics, will be crammed into the second half of the year. Rather than a glut of race-hungry marathoners, we will instead have a glut of runner-hungry marathons.