If Victoria has a home of cross-country, it would have to be Bundoora Park, in Melbourne’s northern suburbs, across the road from LaTrobe University.

They’ve been racing there almost 50 years. For most of that period Victoria has been the powerhouse of Australian distance running, which gives Bundoora Park strong claims as the home of Australian cross-country running, too.

For all that time – and a few years more – Bundoora Park has been a constant in Victoria’s winter cross-country calendar. For road, it has been the Sandown Racecourse motor racing circuit, host to the annual road relays. Over the country, it’s Bundoora Park. The venues for every other winter race have changed regularly; Sandown and Bundoora Park continue year on year.

Not only that, but, the one year when someone thought it a good idea to do some venue swapping excepted, it has always hosted the races over the international distances. Whatever distance is raced at world cross-country – now standardised at 10km for men and women – that’s what we’ve raced at Bundoora Park.

A constant challenge, then, and, likewise, a constantly challenging course. Bundoora Park is one of those never-flat courses. The terrain is always uphill or down. Within that, it offers variety – short and sharp hills, long and grinding ones, stretches where you can never quite find a rhythm, others where you can settle in for a few minutes’ slog or a faster burst downslope.

I say Bundoora Park: more accurately, it’s Bundoora. For the first couple of times I raced the 12km cross-country (as the international distance then was), it was held on the other side of Plenty Rd around the grounds and adjoining fields of Parade College.

When first the race moved across the road, and a little closer to town, at the Park, the women joined the men and we used a different course. But the current 4km loop takes in much the same terrain as the original one did. If anything, as the bottom end of the park has increasingly been turned over to recreation, the loop has been made tougher.

Instead of running towards Mt Cooper, the highest point in suburban Melbourne, the course now passes over the summit before dropping sharply down. Those who are a little ahead of me (which these days is most of the field) will be quick to grasp that, given we are on a closed loop, that means there is an equivalent amount of climbing to come.

What makes Bundoora such a great venue for cross-country racing, though, is that the course is overall neutral. It takes away and gives back in equal measure. There is plenty of uphill running, but not so much that one who is more adept on downhills has no chance. Rhythm is regularly disrupted, but neither so often nor so significantly that a rhythm runner cannot win.

There is mud when it is wet, but the hilly terrain means most of the course drains well. When it is bone dry, good grass cover ensures the surface is not too harsh on the feet.

Over time, Bundoora has regularly hosted national championships and world cross-country selection trials. I had one of my best runs there on a hot January day in one of the selection races.

The first couple of times I raced Bundoora, however, was at the Parade College site. It was in 1977, one of the wettest winters on record in Victoria. The Athletics Victoria cross-country relays had already been held on a shorter loop within the college property. Dick Dowling’s report for Australasian Athletics describes what happened then:

“The relays . . . were held in the worst weather conditions in my experience in a decade of CC running in Victoria. The rain pelted down incessantly and after the first 5000m leg the course was a quagmire . . . About 50 percent of the runners ‘shut up shop’ and merely went through the motions.”

The race was a battle between top two clubs, Glenhuntly and Box Hill, until the latter’s fifth (of six) runners decided the result in spectacular manner.

“As (he) came to a point 80m across from the finish line with about 1000m of his leg left, he threw the baton skywards as his disbelieving clubmates … watched in amazement.”

The baton disappeared into the slurpy swamp that was the college oval.

“And so ended Box Hill’s hopes,” Dowling reported. Quite so.

The 12km, run later that winter, was also over a slop-heap. I came about 70th and was sure my hopes of running the national cross-country were gone. A team of six, plus 20 additionals, would go to Brisbane. In the end, enough ‘additionals’ baulked at paying their own way and I travelled north. Mercifully, I ran a lot better in the dry, warm Queensland conditions.

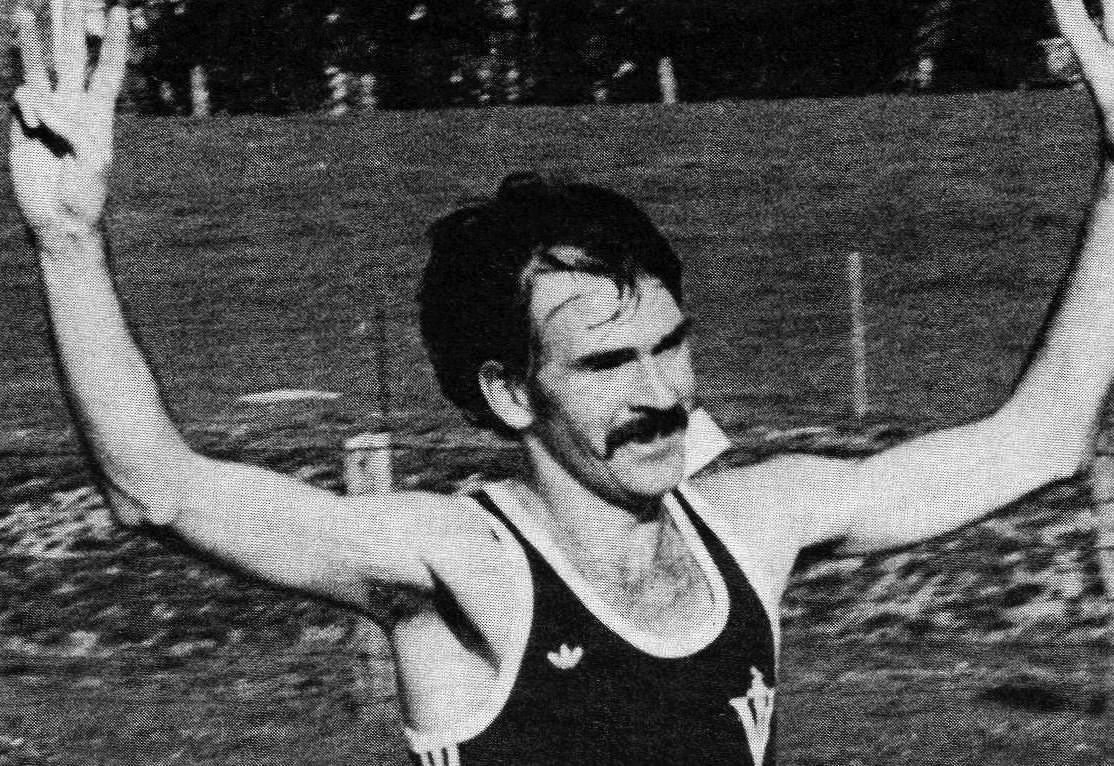

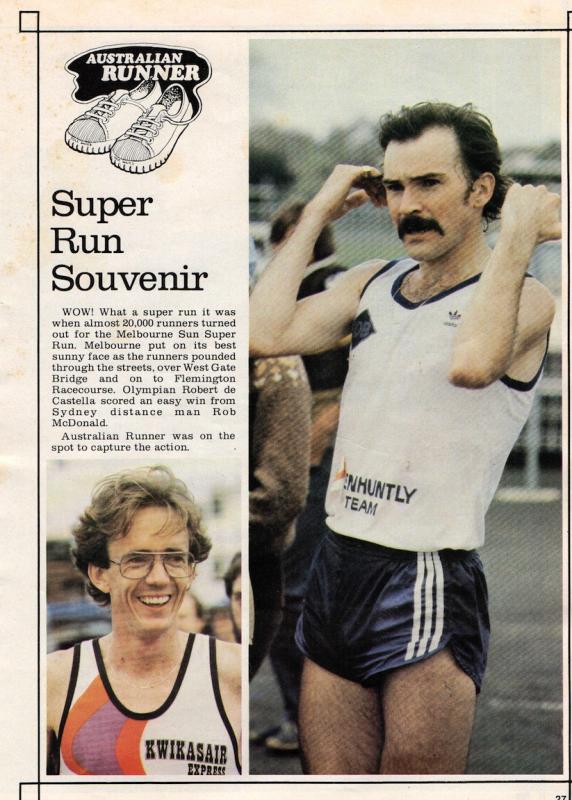

Robert de Castella completed a hat-trick when he won the national title on the original Bundoora course in 1980. Mary O’Connor led three New Zealanders into the first four places in winning the women’s race, with Rosemary Longstaff in second place taking the Australian title.

By the time the championships returned to Melbourne seven years later, we had all moved across the road. Malcom Norwood and Sue Malaxos became the first senior national champions at the ‘new’ Bundoora. Andrew Lloyd and Susie Power were the champions in 1993, the last year Bundoora hosted the nationals (subsequent Victorian hosts have been Bendigo and Yarra Bend (twice each), Geelong and Melbourne’s Moonee Valley racecourse.

About the one thing Bundoora cannot offer is adequate off-course facilities (more’s the pity). It’s strictly tent city, which limits its ability to host a national winter event (again: more’s the pity).

Fortunately, the lack of a hot shower has never been a disqualifying factor when it comes to a place in cross-country history. And Bundoora Park has hosted virtually every notable Australian distance runner of the past half-century. Long may its fame continue.