By Bryan Green,

One of the first bits of “running wisdom” I remember learning is that most records are broken by athletes running negative splits. This means, of course, that the second half is actually faster than the first half.

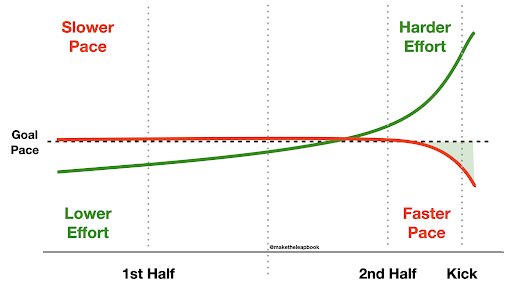

On the surface, this looks like a simple strategy to execute. Just hold your goal pace until you sprint, and then when you finish you will have a faster second half (because of the time you made up at the end) and a slightly better time than your goal. Breakthrough!

Obviously it isn’t that easy. Part of the problem is that we tend to think of pace and effort as having a linear relationship. Renowned running coach Greg McMillan summarized this eloquently in our recent Fueling the Pursuit conversation:

“Most everybody’s good halfway through their race. It doesn’t matter if it’s an 800-meter race or it’s an ultra marathon. It’s sort of like the first half everybody’s kind of happy, but then something after that starts to happen where you’re still too far out from the finish line to really feel like you can push. But if you stay at the same effort level, you will slow down because your effort level has to increase at a faster rate than you wish it did because fatigue is increasing.

If you think about fatigue, it’s not a straight line across a race. It’s not even any sort of angle of a straight line. It is exponential. Just after halfway, the effort and the fatigue start to ramp up even faster than it was before.”

In other words: since fatigue isn’t linear, you can’t run a consistent pace by trying to sustain a consistent level of effort.

Why consistent effort results in positive splits

When we assume the effort required gradually gets harder, we set ourselves up to run positive splits. That’s because our energy isn’t being used up along a linear curve. We’re going to feel more tired at the halfway point than we expect.

This is true of any race distance but it was always particularly apparent for me when I raced the mile. I was a 5k/10k guy, so I enjoyed the mile as a “short race.” But I found it so hard to stay on the pace in the third lap. I would hit 800 meters at what felt like a reasonable time but my body was already screaming to just hold my effort, to save a little for the end. When I did, I always ran a slow third lap.

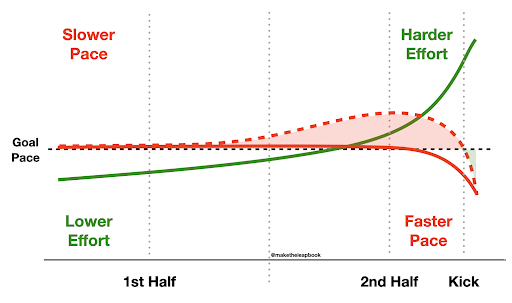

I see this with many runners. Even if we gradually increase our perceived level of effort, our fatigue increases faster and our pace starts to slip. And as we get more and more tired, we keep telling ourselves to just hold on, and we slow even more. Then we kick it in and regain some of the time we lost, but not enough to get negative splits or, often, our goal time.

I see this with many runners. Even if we gradually increase our perceived level of effort, our fatigue increases faster and our pace starts to slip. And as we get more and more tired, we keep telling ourselves to just hold on, and we slow even more. Then we kick it in and regain some of the time we lost, but not enough to get negative splits or, often, our goal time.

As you can see in the second diagram, the red section above the line (our time lost) is far greater than the green section below (our time gained).

Use a “Go Zone” Racing Strategy to Get Negative Splits

Coach McMillan has a mental strategy to combat this. He calls it “Go Zone Racing.”

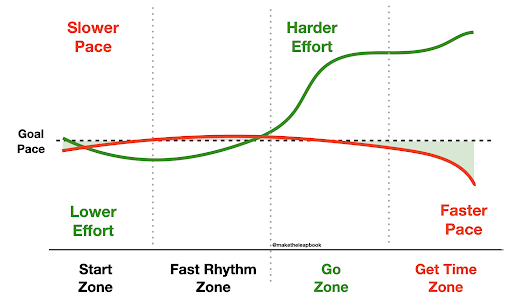

He breaks up a race into four quarters or “zones”: Start Zone, Fast Rhythm Zone, Go Zone, and Get Time Zone. He prepares his athletes to have a specific plan for each of these zones, in order to be mentally prepared for how they will need to execute in each.

He’s written about this in numerous articles (here is one from 2009) but I recommend you pick up his new book Running Nirvana: 50 Lessons to Elevate Your Running. It not only goes into this idea in detail, it includes insightful lessons on literally every key aspect of training and racing. I picked up a number of useful ideas, and have even improved my pre-run mobility routines as a result.

The key insight to Go Zone Racing is that the third zone just after the midway point–what he calls “the Go Zone”–is where most athletes fail to maintain their pace and miss their opportunity to hit their goals.

The only way to combat this is to have a plan to go hard in this zone. Harder than we’ll be comfortable and harder than it feels like we “should” need to go in order to stay on pace. As he put it:

“What we find is that athletes need to ramp up their mental intensity, their effort level, in order to combat that fatigue and stay on pace. Because if you have increasing fatigue at the same effort level, you’re going to slow down.”

Our effort needs to look more like the green line in the below chart. And yes, our pace will likely only stay at goal pace despite this tremendous effort. That’s the painful reality our mental racing plan needs to prepare us for.

Of course, this still only gets us three quarters of the way there. In the final quarter–the “Get Time Zone”–we need to hold that effort and use every trick in the book to keep us moving faster than we feel we can go. If we really want to run a fast time we can’t wait until the kick. There isn’t enough time to make up in the last 200 meters. To really get those negative splits, we need to make up more time earlier.

Of course, this still only gets us three quarters of the way there. In the final quarter–the “Get Time Zone”–we need to hold that effort and use every trick in the book to keep us moving faster than we feel we can go. If we really want to run a fast time we can’t wait until the kick. There isn’t enough time to make up in the last 200 meters. To really get those negative splits, we need to make up more time earlier.

Let’s Go!

Go Zone Racing is very much a strategy for running your best race. But Coach McMillan doesn’t put it in his section on Racing. He puts it in his section on Brain Training.

That’s because it isn’t just a tactic you can utilize at will to run a better race. It’s a way of approaching workouts and races that requires incredible mental preparation and commitment to execute.

There’s a reason most runners don’t run negative splits. It’s not just because it’s really difficult. It’s because even if they are physically ready, they often aren’t mentally prepared for the effort it takes. Make sure you are.

About Bryan

Bryan Green’s book, Make the Leap: Think Better, Train Better, Run Faster, has been praised by Olympians, coaches, and competitive runners as “a pathway book” that “should be on the shelves of every coach and athlete.” You can purchase the book, workbook, and coach’s guide or sign up for his weekly newsletter at his website. Bryan is also the co-founder of Go Be More, co-host of the Go Be More Podcast and Fueling the Pursuit, and has been a frequent contributor to Runner’s Tribe (dating back to 2008!).