By Len Johnson

The first time I went to Japan to run the Fukuoka marathon my feet didn’t touch the ground until the five-kilometer point of the race.

Until then, the whole experience had been surreal. Most marathoners will be familiar with other-world feelings towards the end of the race. The sole aim becomes maintaining pace and form. The mind shuts out pretty well everything else, as the focus shrinks to getting to the finish line the best way you can.

I had entered this surreal world a few days earlier, however, the minute the plane from Tokyo touched down in Fukuoka and we headed to arrivals. Customs clearance is always a necessary drag, but the moment it emerged we were there for the marathon our bags were snapped closed and we were waved through.

Same thing at the Nishitetsu Grand Hotel, the accommodation for the international competitors. Expedited check-in, bags transported to our single rooms. Fukuoka then had a strict qualifying time of two hours 27 minutes. Every international entrant was an ‘elite’. Some were more elite than others, but entry-level elite was more than good enough for one such as I, whose previous three marathons had involved driving to Point Cook, the Royal Australian Air Force training base on the edge of Melbourne and racing around the back roads of Werribee.

Only when I saw the split time for the first five kilometres – 15 minutes 50-something – did reality come crashing back in. My entry time was 2:23:56, run in Australia’s Commonwealth Games selection trial some seven months earlier. That had been a personal best by some ten minutes. My aim was to go sub-2:20 in Japan, but quick mental arithmetic told me I was on track for something in the 2:13-15 range.

Back off a little, I told myself, stealing a quick glance over my shoulder to check out how many competitors were behind me. No more than handful, it turned out. It was either maintain this pace or run on my own. I may not have been ready for 42km at this pace, but nor was I ready to run 37km solo.

Back off a little, I told myself, stealing a quick glance over my shoulder to check out how many competitors were behind me. No more than handful, it turned out. It was either maintain this pace or run on my own. I may not have been ready for 42km at this pace, but nor was I ready to run 37km solo.

Regular readers will know I’m a great fan of the Fukuoka marathon. I ran there twice, and they were my two fastest marathons: 2:19:32 in 1978 and 2:20:18 the following year.

Now, as then, and almost without exception throughout its history from 1947, Fukuoka was run on the first Sunday in December. Sunday, 5 December, 2021 will be the 75th, and last, Fukuoka.

From a local Japanese race, Fukuoka rose to the status of unofficial world championship. Always, though, it remained a race for the elite, even as those elite were reduced largely to local runners – albeit from the seemingly bottomless national pool of Japanese marathoners – and Japan-based Africans.

For years, Japan’s championship selection process centred around its elite marathons – Fukuoka, Beppu and Lake Biwa for the men; Osaka, Nagoya and Tokyo women’s for the women. Over time, the separate Tokyo men’s and women’s races were transformed into the mass-participation Tokyo marathon and performances there took on greater importance for national selection. Fukuoka, the most prestigious of any of the Japanese Federation-supported marathons, held out the longest.

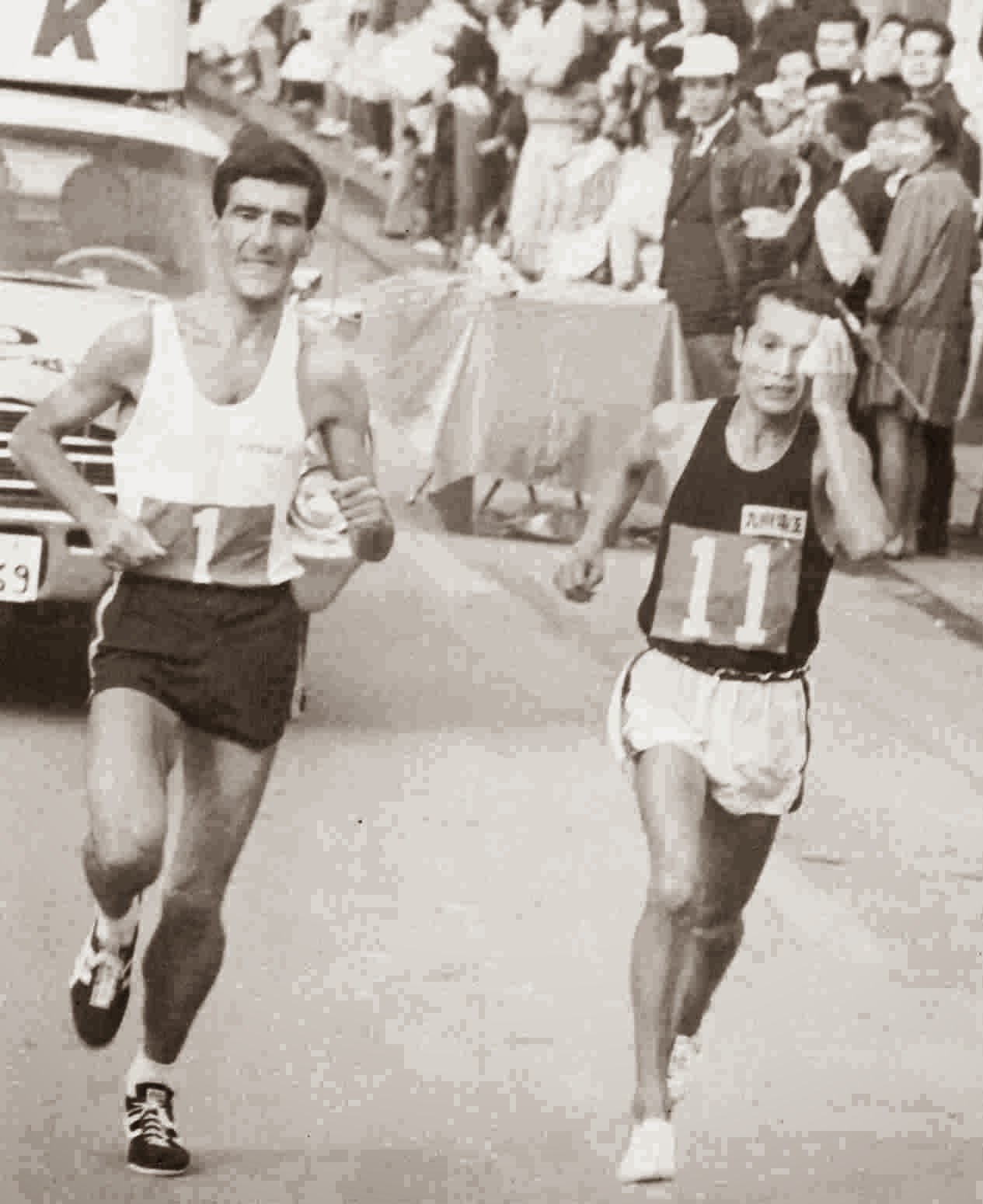

If Fukuoka is now history, however, at least the race has a magnificent story to tell. In the first phase, from 1947 to 1965, it was a local race sponsored by the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, one of Japan’s five major media corporations. Some internationals competed, including Australia’s Rod MacKinney who, in 1966, ran 2:19:06, becoming the first Australian under two hours and 20 minutes.

In 1966, the race restyled itself as the Fukuoka International Open Marathon Championship. I ran the thirteenth and fourteenth editions in 1978 and 1979.

Fukuoka adopted a simple modus operandi, invite the best six international and best six domestic runners available while setting a strict entry standard on the rest. The race also explored arrangements with national federations in Eastern Europe and Africa to ensure a steady supply of top runners. When the only truly international championship was the once-every-four-years men’s Olympic marathon, Fukuoka’s philosophy and end-of-year timing ensured its rise to ‘unofficial’ world championship status.

Which brings me back to 1978. The field contained the reigning Olympic champion (Waldemar Cierpinski), the 1978 European champion (Leonid Moseyev), the 1978 Boston and New York winner (Bill Rodgers, the winners of the three most recent Fukuoka races (Rodgers, 1977; Jerome Drayton (1975-76) and three others of the top-10 finishers in the European championships. Among the locals were Toshihiko Seko (the ultimate winner), the Soh twins, Shigeru and Takeshi, Kunimitsu Itoh and Hideki Kita.

Which brings me back to 1978. The field contained the reigning Olympic champion (Waldemar Cierpinski), the 1978 European champion (Leonid Moseyev), the 1978 Boston and New York winner (Bill Rodgers, the winners of the three most recent Fukuoka races (Rodgers, 1977; Jerome Drayton (1975-76) and three others of the top-10 finishers in the European championships. Among the locals were Toshihiko Seko (the ultimate winner), the Soh twins, Shigeru and Takeshi, Kunimitsu Itoh and Hideki Kita.

Before that, Frank Shorter had won four times in a row from 1971 to 1974 either side of his Olympic gold medal In Munich in 1972.

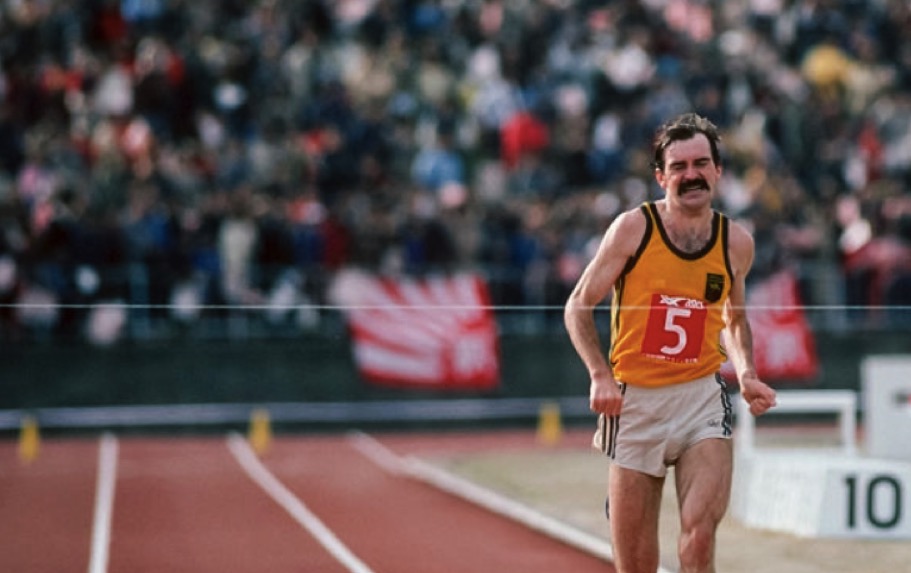

Australians have set three men’s marathon world bests/records, two of them at Fukuoka; Derek Clayton won in 2:09:36 in 1967 and Rob de Castella in 2:08:18 in 1981. Numerous Aussies have placed high and/or set PBs there including – a non-exhaustive list – John Farrington, Dave Chettle, Garry Henry, Chris Wardlaw and Bill Scott.

There’s plenty of official history of Fukuoka, but to convey some of that surreal feeling I experienced in 1978, let’s check my diary.

Chris Wardlaw and I arrived the Wednesday before the race. Of our first run that afternoon, I wrote: “Ran with everyone”. ‘Everyone’ included Rodgers and Tom Fleming and Trevor Wright, Britain’s 1971 European championships silver medallist.

Next day was course inspection: “Ran 10km with Chris, Trevor, Waldemar Cierpinski and Joachim Truppel.” Friday was 16km around Ohori Park and Fukuoka Castle. Ohori Park was the local version of Melbourne’s Tan, packed with locals who came buzzing past at eyeballs-out pace. That night, I mentioned to our interpreter that my calves were a bit tight. Saturday morning, I was whisked off to the local hospital for therapeutic massage.

Finally, there was a press conference for the internationals at which all the English-speaking internationals – including me – were at the top table.

Actually, given these circumstances, it was an achievement to hold myself back to 2:14-15 pace.

My marathon didn’t end as well. For all but the best of us they rarely do. Regularly passing those who had gone out even faster, I picked my way up from near last of the 100-plus starters to twenty-second, running a personal best 2:19:32. Chris Wardlaw led at half-way on world record pace before finishing seventh in 2:13:02.

That night, the international athletes’ liaison Mr Shibuya, took the English-speaking internationals out to a banquet of noodles accompanied by drinks and followed by some clubbing. The race could have gone better, I reflected, but the experience was incomparable.

Farewell to Fukuoka, then. I hope we see your like again, but I suspect we won’t.

Great article Len! Love the insight into a world very few of us will ever experience. Just one thing, I thought Jeff Hunt’s 2:11 was run at Beppu-Oita?

Great article, however the photo of Jeff Hunt stating he ran 2.11 at Fukuoka in 2.09 is not correct. He ran that time in Beppu marathon in 2010.