This article was written with the help from Snell’s classic book, NO BUGLES NO DRUMS

Profile

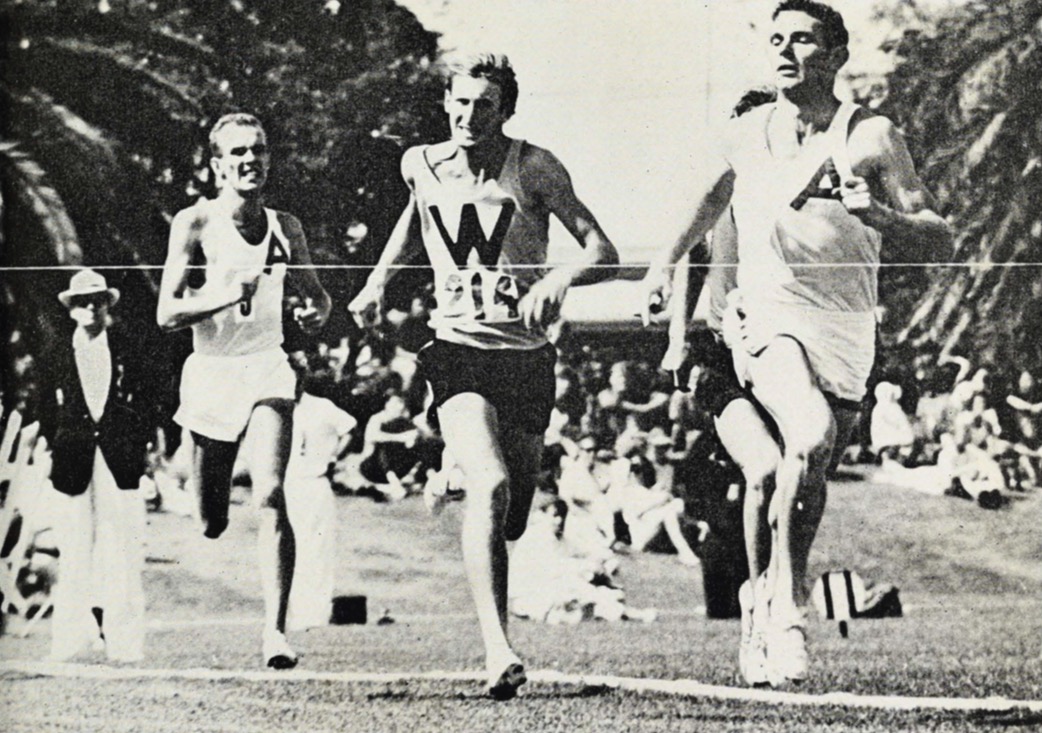

Snell won three Olympic gold medals during his career, including winning both the 800 and 1500 metres at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

- Born: 17 December 1938, Opunake, New Zealand

- Died: 12 December 2019, Dallas, Texas, United States

- Previous World record over 800, 1000m & Mile.

- Olympic 800m Gold, Rome, 1960.

- Olympic 800m Gold, Tokyo, 1964, a new Olympic record.

- Olympic 1500m Gold, Tokyo, 1964.

Personal Bests

- 800m: 1:44.30

- 1000m: 2:16.60

- 1500m: 3:37.60

- Mile: 3:54.1

Lydiard’s Man

Snell was arguably Lydiard’s most famous athlete. Lydiard took Snell from an average school grade runner to one of the best middle distance runners the world has ever seen. His 1:44.3 world 800 metre record set in 1962, on a grass track, still stands as one of the finest 800m performances of all time.

Through Lydiard’s training methodology Snell became an extremely strong runner. He covered distances in training that was unheard of at the time, and even to this day is considered on the extreme side.

Marathon Conditioning

Under Lydiard’s instructions, Snell undertook an extensive period of base building which consisted mainly of long runs. In the book ‘Running with Lydiard’ By Lydiard and Gilmour, it explains the purpose behind this marathon conditioning stating that:

“The fundamental principle of training is simple, which may be why it needs repeating so often: it is to develop enough stamina to enable you to maintain the necessary speed for the full distance at which you plan to compete. Many runners throughout the world are able to run 400 metres in 46 seconds and faster; but remarkably few of them have sufficient stamina to run 800 metres in 1:44, or 52 seconds for each 400 metres. That clearly shows the part stamina plays in middle and distance running. It is absolutely vital” – Arthur Lydiard

More precisely, this marathon conditioning phase consisted of Snell running approximately 160 kilometres per week at his near-best aerobic effort. However, Snell was also encouraged to complete other runs at a slower pace. Lydiard writes:

“My middle-distance men, Snell and John Davies, were running the lowest total weekly mileages but even they were covering about 250 kilometres a week” – Arthur Lydiard

In Snell’s biography ‘No Bugles, No Drums’ Snell describes his build-up training the winter before the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Snell states that he would run 90 minutes every morning and then do other runs throughout the day. However, on a Sunday he would without fail run the 22-mile hilly course through the Waikati ranges. Snell also states in his book that even though Lydiard demanded 100-mile weeks from him he was not able to handle that many miles week in week out and often when he hit a flat patch the total mileage might have dropped to around the 80-mile per week level.

The marathon conditioning phase lasted as long as possible; the standard for Snell would be approximately four months.

Speed and Anaerobic Training

At the end of the marathon conditioning period Snell launched into a period of speed and aerobic capacity development, through the use of hill and speed orientated interval sessions.

Lydiard’s theory cantered around the belief that:

“No-one and no training can make a basically slow runner into a basically fast runner. Greater speed can be developed to a limited extent, but the basically slow runner will remain a basically slow runner in relation to other runners” – Arthur Lydiard

Thus meaning that runners should choose the distance that they would race over depending on their speed. Snell had decent, yet not brilliant speed; his personal best for the 200m was 22.3 seconds.

Training Specifics

The best way to outline Snell’s training is to examine his training during 1964 leading into the Tokyo Olympics.

By April 1964, Snell was a bit flat and needed more basic conditioning to prepare for the Tokyo Olympics to be held in October 1964.

From April 18th until June 28th 1964, Snell averaged 100 miles per week on average. It is interesting to note that Snell actually split with Lydiard in late 1963 to early 1964 and he actually set his own training schedule thereafter. Lydiard continued to observe and advise when Snell requested his assistance. From ‘No Bugles No Drums:

March 1964: “Arthur doesn’t advise Pete on his training any more but Pete has frequently gone to him to talk about his condition and progress and Arthur has always willingly given him the same psychological encouragement which he gives to his other athletes.” – Sally Snell, Peter’s wife.

This explains Snell’s training from the horse’s mouth:

April-August 1964

“I realised my need to get in as many miles as possible in training. Stamina was going to be the key in Tokyo.

I began running twice a day-half an hour in the mornings and an hour and a half at night-aiming to reach 100 miles a week as soon as possible. I made it after two weeks, training mostly with Barry Magee, an ideal companion because of his ability to maintain a uniform pace and his willingness to increase the pace when I wanted to push it.

I could never run more than three consecutive weeks of 100 miles but over 10 weeks I logged a total of 1012 miles – the greatest amount of distance running I’ve ever done. And, whatever my progress during the week, I made absolutely certain that I covered the 22-mile Waiatarua circuit every Sunday right through the 10-week period. That was one part of the training I couldn’t afford to miss.

I approached this distance build-up carefully, studiously avoiding any speed running. I was well aware from experience of the pitfalls such as leg injuries that excessive speed could produce.

I spent a lot of money on shoes and I concentrated purely on mileage. I don’t think I ever ran faster than six-minute miles, although my speed increased naturally as I got fitter and stronger.

At first, I took an hour and 45 minutes for 15 miles. After six weeks, I ran 15 in 1:30 and 18 in 1:52. And I cut my Waiatarua time from 2:25 to 2:15, with the odd one in 2:12. I rarely ran two hard sessions together. I would try six-minute miles one night and seven-minute miles the next to make sure I was, in fact, building up and not draining out.

I bought a special nylon jacket to wear in wet weather and kept the cold out by rubbing olive oil on my legs. I took more than usual care of myself this winter to counter muscle trouble. I was also taking a balanced vitamin pill because the previous winter I’d caught a cold and then developed ‘flu which cost me two weeks. It was vital now that I missed no training.” – Peter Snell

Snell then did a lot of hill training from June 29th until August 9th. During this period his average mileage was approximately 90 miles per week.

“From the distance running, I moved into a six-week training session on the hills, which finished nine weeks before the Tokyo races” – Peter Snell

On August 10th, Snell then commenced track training.

Snell had the following to say about this:

“My track work began sensationally with 20 quarters in an average of 62.5 seconds. I had hoped for something like 65 seconds and it was a terrific boost to me to know that I’d gained so soon the rhythm of running at this pace. I kept at it by doing a great deal of short, sharp sprint work.” – Peter Snell

Training Diary Leading into Tokyo

The below training diary has been sourced from Lydiard’s training diary and from ‘No Bugles No Drums’. The below diary represents Snell’s speed training during the two months leading into the Tokyo Olympics.

August 1964

Each morning Snell ran approximately 5 miles on a golf course or road.

- August 10th: 20 times 220m. Average 27.45 seconds.

- August 11th: 3 miles time trial in 14.47.6.

- August 12th: 660m in (1:27). Then 2 sets of (11 by 100 yard sprints)

- August 13th: 3mile time trial followed by some 50yard sprints.

- August 14th: 6 times 220m. Average 26.5 seconds.

- August 15th: 20 times 440. Average 61 seconds.

- August 16th: 22 miles Waiatarua in 2 hours 22 minutes.

- August 17th: 20 times 220m. Average 27.8 seconds.

- August 18th: – 3 mile time trial in 14:35.

- August 19th: – 5 times 880m. Average 2.13.

- August 20-22nd: – Injured leg due to running on a hard track. No training.

- August 23rd: – 22 miles in 2h 33 minutes.

- August 24th: – 5 mile jog.

- August 25th– 27th leg still sore – no training.

- August 28th: 4 times 440m stride-outs.

- August 29th: – 6 mile jog.

- August 30th: – 22 miles in 2hr 23 min.

- August 31st: 220 stride-outs.

September

Each morning Snell ran approximately 5 miles on a golf course or road.

- September 1st: 6 times 880m. Average 2:10

- September 2nd: 6 times 440m. Average 58.0.

- September 3rd: 1 mile at half effort, then 1 mile three quarter effort.

- September 4th: 3 times 220m sprints.

- September 5th: 880m. Cold wet conditions. 2:01.

- September 6th: 22 miles easy

- September 7th: 1 mile hard followed by some 50 yard sprints.

- September 8th: – Three quarter mile. Then880 in 1.56 with the final 440 as he felt.

- September 9th: 440m in 55seconds. Then 4 times 100yard sprints.

- September 10th: 2 times 1 mile at half effort.

- September 11th : 3 times 220 yards at full effort

- September 12th: 10 times 440m averaging 58.5 with a lap jog recovery.

- September 13th: Long run

- September 14th: 10 miles morning. In the afternoon, 4 times 150yards and 6 times 50yard sprints.

- September 15th: 2 times 880 yards, windy and wet. 2:02 and 2:01.

- September 16th: 10 miles morning in the morning. In the afternoon 3 mile time trial in 14:12.

- September 17th: 6 times 440 yards in 58.0.

- September 18th: 3 times 220 all out sprints.

- September 19th: Three quarter mile time trial in 3:05

- September 20th: 20 mile run at an easy effort.

- September 21st: One hour jog

- September 22nd: 6 times 220 yard stride outs

- September 23rd: One hour jog

- September 24th: Flew to Sydney – 6 times 220 stride outs

- September 25th: – 660m time trial between Snell and John Davies in 1:19.

From No Bugles No Drums:

“We fitted in a 660 yards race between John and me. I was feeling quite fresh from a week of relatively easy training and decided it would be to my advantage to run a fast quarter in about 53 seconds and then hang on for the rest.

We both passed the quarter in 53 seconds as planned and I stayed in front for a final time of around 1:19” – Peter Snell

- September 26th: – Flew to Japan.

- Snell jogged most mornings in Japan before breakfast for at least 30 minutes: From No Bugles No Drums:

“We wanted to run for at least half an hour every morning before breakfast” – Peter Snell

- September 27th: One hour jog.

- September 28th: 20 times 220 yard stride outs.

- September 29th: 1 mile of 50 yard dashes.

- September 30th: Three quarter mile time trial in 2:56.

October

- October 1st: 2 hour run – strong and even pace.

- October 2nd: 4 times 440 yard efforts.

- October 3rd: 6 times 880 at half effort. Averaged 2:05

- October 4th: 1 mile time trial in 4:02

- October 5th: 10 times 220 stride outs

- October 6th: Sprint training over 150 yards.

- October 7th: 800m fast time trial in 1:47.1

- October 8th: 1 hour jog.

- October 9th: 880 yard in 50yard dashes.

- October 10th: 1 hour jog

- October 11th: 3 times 220 yard sprints.

- October 12th: 1 hour jog

- October 13th: Half an hour jog

- October 14th: 800m heat. 1:49

- October 15th: 800m semi. 1:46.9

- October 16th: 800m final. 1:45.1 Olympic Gold.

- October 17th: 1500m heat. 3:46.6

- October 18th: 1 hour jog

- October 19th: 1500m semi. 3:38.8

- October 20th: 1 hour jog

- October 21st: 1500m final 3.38.1 Olympic Gold.

Some Snell viewing.

New Zealand National Film Unit presents Peter Snell, Athlete (1964)

Peter Snell 50 years since Tokyo 1964

Men’s 800m and 1500m Tokyo 1964 highlights (Peter Snell Documentary)

Love it! It would be great to get additional commentary around each section of the book from Peter Himself. Maybe a writer could record the conversation, summarise and add it as an addendum between each chapter on his views today looking back. It would be great to have for posterity, he will be 80 years old in 2018. Long may he live!

The greatest middle distance athlete ever to pull on a pair of spikes. Talented: yes. Worked hard: yes. WRs on grass and cinders and uncontested. Based on how he ran his first mile WR 3.54.4 in 1962 (last 880 in 1.53.8) and half mile WR (last 220 in 28.2!!) could have run much faster for both distances in his career. But he was primarily a racer – competitive record proves it and in Tokyo was supreme. Nobody better, then or now. Great Book – a lot of learnings within for middle distance runners if they take the time to read it.

Some small errors in this article, namely with regard to Maori placenames. For instance , the famous 22-mile Waiatarua hill circuit was run in the Waitakere ranges to the west of Auckland City. I think the ’22-mile hilly course through the Waikati ranges’ is a scrambled approximation of the Waiatarua circuit that runs through Auckland’s Waitakere ranges.

Another thing not remarked upon nearly enough; Snell managed to run his world mile record of 3:54.4 on grass 6 weeks and 6 days after completing his first and only competitive marathon, the local Owairaka marathon, run on on a warm Auckland day on Dec 9th, 1961.Then, only another 7 days after that world record, he ran the sensational 1:44.3 world record 800m on grass, which is still the New Zealand record despite synthetic tracks, John Walker and Nick Willis having emerged in the 59 years since.

Being the ultimate competitor, but definitely not being a ‘natural’ distance runner by inclination, with no great love of the very long runs until he was ‘endurance conditioned’, Snell and Lydiard deliberately targeted a marathon race in mid-summer, knowing full well that unless he had a full marathon race in his immediate sights, he would be unlikely to stick to the high mileage aerobic training schedule required to amass the necessary aerobic conditioning. All of the regular training partners of Peter Snell alive today could affirm that Snell had an intense dislike for the long hilly run, but despite this intense dislike of the distance, he knew that it was extremely good for his eventual anaerobic performance capacity, and very rarely did he ever miss a scheduled long Sunday run.

Barry Magee, who ran the long Waiatarua course with Peter Snell more than all the other athletes, said that in his first few weeks of aerobic conditioning, Peter would be ‘struggling’ to keep up with the regular long-run pack, but after persisting for a few more weeks, Peter’s aerobic endurance capacity started to kick in, and he started to “be hard to hold onto” in the long runs. (Physiologically, constant exposure to moderate intensity aerobic running for about 10 or more hours of easy running a week would stimulate VEGF, or vascular endothelial growth factor, which in turn promoted angiogenesis, or the formation of entirely new capillaries deep into the running muscles exercised, and the same process engendered mitochondrial biogenesis deep into the same muscle fibres as well, by stimulating the enzyme cytochrome C.)

Aerobic enzyme levels would’ve increased almost exponentially with several months of this sort of running.

Despite correctly citing Snell’s own words regarding his aerobic training volumes from his autobiography in this article,(where Snell maintained that his best block of aerobic conditioning volume totalled 1012 miles in ten weeks), a less than helpful additional quote from Arthur Lydiard himself muddies the waters considerably. In fact, Lydiard is quoted from one of his own training books as saying: “My middle-distance men, Snell and John Davies, were running the lowest total weekly mileages but even they were covering about 250 kilometres a week”. There’s a world off difference between 100 miles a week (161 km/wk) of running, and 250 km/wk. in terms of potential for long-term joint damage and total glycogen depletion.

Unfortunately, as absolutely great as he was, Arthur still had a garrulous way of saying things on frequent occasions to simply emphasize a point. That was Arthur’s way, and I don’t believe that simple throwaway statement served his cause well, because from Peter Snell’s own highly detailed account he never claimed to run that much volume, and would probably have been quite annoyed to see claims like that made in such an off-hand manner. Certainly this tendency of Arthur’s to say things ‘off the cuff’ or ‘exaggerate’ was a source of conseiderable friction to the more self-effacing Peter Snell.

On that specific matter, I was discussing this exact claim by Arthur with Bruce Milne, a former New Zealand Olympic team distance coach, who was a very good friend of Arthur Lydiard,and also a very good friend and coaching colleague of the late John Davies, a couple of years ago during a visit to Christchurch. Bruce told me he had asked John Davies if this particular claim by Arthur was true a number of years ago, and John went to the trouble of digging out his old training diaries and totalling up his training volumes, because he wasn’t sure himself. To make a long saga short, Davies’s best recorded volume of aerobic training in a long aerobic training block totalled an average of about 85 miles a week, but like every other Lydiard athlete that 85 miles each week religiously included the weekly long run of 22 miles. Runs of that duration at moderate aerobic intensity have been shown to increase mitochondrial density significantly.

Snell’s autobiography is quite self-effacing to an extent; he glossed over what were arguably his most phenomenal running performances ever, done well away from the track, in winning the Auckland 10000m cross-country title over the very hilly Cornwall Park course, outkicking multiple national distance and cross-country running champion, 3:59 miler and Olympian Bill Baillie in the last few metres, as well as Olympic medalists Halberg and Magee; then repeating the dose a month later in the national title where he won by about 40 seconds from another top national field. What would we make of it today if we had a young 800m runner who was able to run like that against top-level national competitors within months of running world middle-distance records?