The world of Formula 1 is the pinnacle of technology and engineering in motorsport. As a result, it is regularly used as a comparison to developments in other sports. Whenever there appears to be an excess in technology, analogies to F1 appear as a way to decipher whether or not the advancement is innovation or an overstep.

In the case of athletics, there have been a number of comparisons to F1 since the introduction of Nike’s VaporFly technology. Even Eluid Kipchoge, the fastest marathoner on the planet and the Nike flagbearer had some bizarre comments regarding Pirelli tyres and World Champion Lewis Hamilton:

“There are 10 teams in F1, with the great engines, and the great tyres from Pirelli but only Lewis Hamilton is winning. Why? Because he is focused and he’s a very good professional driver. I met him in Abu Dhabi and realised that to win it’s not the tyres, it’s the person.”

This type of deconstructed comparison between runner and driver, shoe and tyre and so on fails to provide any significant insights given that an F1 car has around 80,000 components. Yet there is a theme that can be traced between both F1 and athletics; the complex and often controversial relationship between innovation and regulation.

The controversy surrounding carbon-fibre plates and the Nike VaporFly mirrors a situation that unfolded over 25 years ago in F1: The introduction of active suspension and the ensuing dominance of the infamous Williams FW15c.

THE FORMULA

Analogies break down when a clear frame of reference isn’t provided, so here is mine:

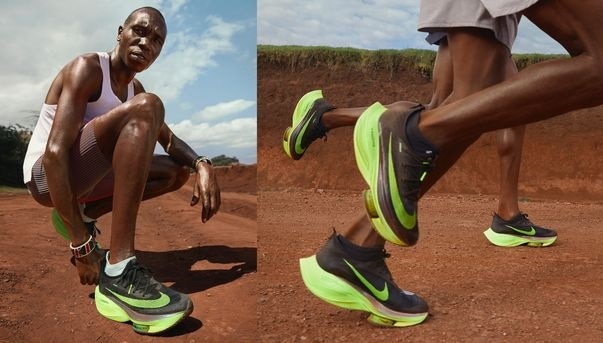

I am a fan of both F1 and athletics, but they cannot truly be compared. As a result, this is essentially all conjecture; it is an exercise undertaken for personal interest, not peer-review. I have worn every version of the VaporFly since 2016, having also tested various versions of the AlphaFly NEXT% over the past 2 years, but am not making a case for or against the regulation of any technology mentioned. I am comparing scenarios between two very distinct sports.

Moreover, active suspension was only one of eight electronic aids onboard the Williams FW15c, but is the particular system that the discussion is focused on.

MAKE OR BREAK

The Formula in Formula 1 is the set of rules and regulations laid out by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) that teams must comply with. In the sport of running, we’ll consider that to be the equivalent of World Athletics and their rules governing competition footwear.

In F1, engineers have always tried to outwit those who write those rules – it’s almost an accepted part of the sport. In athletics, the closest comparison to this game of cat and mouse is the role carried out by anti-doping authorities. However, with the introduction of Nike’s AlphaFly NEXT% and its predecessors (and competitors), the sports rule-makers have an entirely new field of performance aids to discern and legislate.

This situation is not unlike that which the FIA found itself in during the 1993 season with the introduction of electronic driver aids. The team that received the most attention was Williams, with the British team refining the use of active suspension as part of the FW15c.

SETTING THE STAGE

At the time of the FW15c, active suspension was not a new idea. The system had been implemented in various forms since Lotus first introduced it in 1983. In fact, Williams had even used it in 1992 – convincingly securing both the driver and constructors championship.

As Williams dominated the season, rival teams were forced to research and develop their own variations of the technology or be left behind.

CRACKING THE CODE

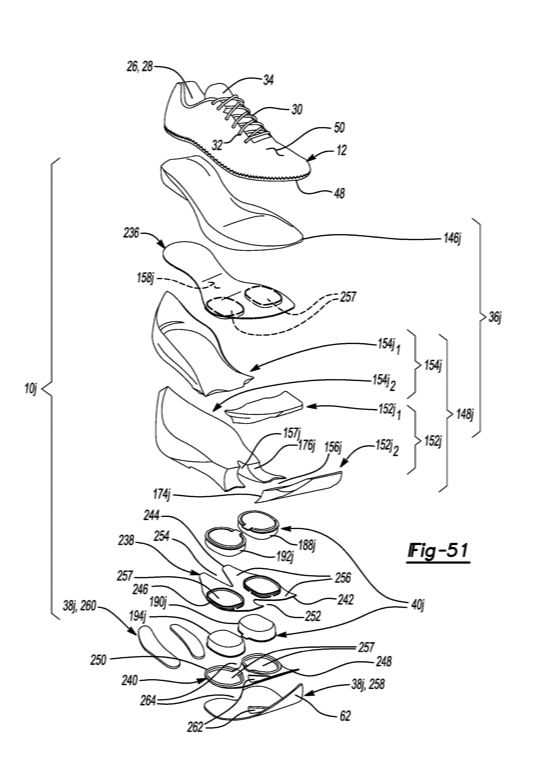

With traditional suspension, the position of an F1 car is determined by variations on the track/road surface – it’s essentially reactive. However, these undulations result in costly losses of speed and grip due to the height of the car constantly changing.

Active suspension utilised hydraulic actuators on each wheel that adjusted independently of each other, modifying the cars relationship to the track and ensuring the most stable aerodynamic platform at all times. The complex system utilised electronic controls that could apply corrections in real-time based on information received from the onboard sensors.

In 1993 it became clear that Williams had done more than simply update their active suspension from 1992, they had unleashed it. The FW15c provided a 12% increase in aerodynamics over its predecessor, and to this day is regarded as the most technologically advanced F1 car ever built.

The effect on the track was extraordinary. The two Williams drivers Alain Prost and Damon Hill regularly qualified 1.5 – 2.0 seconds ahead of their nearest rivals, Aryton Senna and Michael Schumacher. Yet without the computer powered data processing onboard, the car would have been impossible to drive. It was at this time that the line between driver skill and technology began to seriously overlap.

THE VAPORFLY EFFECT

Nike didn’t invent the concept of a carbon-fibre plate within a racing shoe, but just as Williams had done with active suspension – they were the ones to weaponize it.

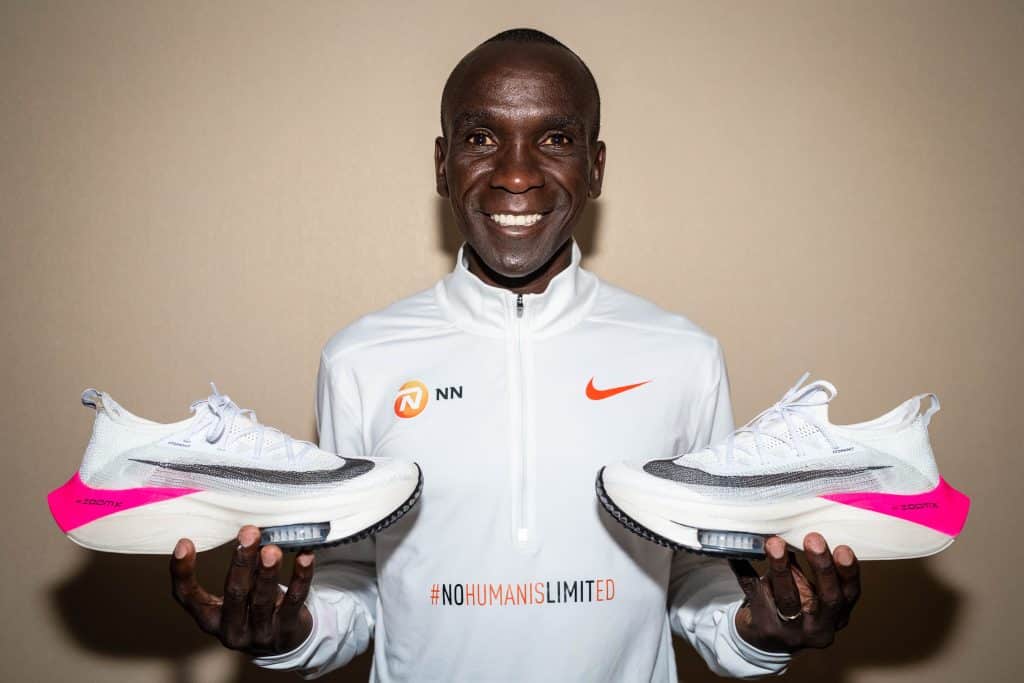

Many athletes have the VaporFly, but Eluid Kipchoge is its flagship athlete, having become synonymous with its success. He was the first to truly put its significance on the map – on a Formula 1 track of all places. However, his accomplishments with the technology cannot be measured in victories alone. Kipchoge may have never lost a race in the VaporFly, but he had only failed to win 1 marathon prior to that point.

Rather, it’s the dominant fashion by which he has brushed aside his competitors and the speed and consistency he has maintained in doing so that has been so impressive. It isn’t only that he seems unbeatable, he seems unstoppable.

COMMAND AND CONQUER

When an extraordinary talent is armed with groundbreaking technology, performance escalates by an order of magnitude. In 1993 Alain Prost convincingly won the World Championship – finishing on the podium in 12 out of the 16 races that season, winning 7. The FW15c qualified fastest in all but the last event of the season in Adelaide, setting a record of 15 straight pole positions. At the Australian GP Aryton Senna led from pole in what would be the final win of his career, and the last race he would ever finish.

Driving next to Prost in the second FW15c was 33 year old Damon Hill, who would go on to finish 3rd in his first full season of F1. With 10 wins from 16 races Williams dominated the constructors championship, finishing the season with 168 points to McLaren’s 84.

1993 would be Prost’s last season in F1. But, like Kipchoge, Prost had nothing to prove. Both were champions before the technological interventions and had already established themselves in the conversation of all-time greats.

Even when considering the unique differences between the sports, Kipchoge’s performances alone don’t provide enough context for a clear comparison to the impact of active suspension on the FW15c. However, collaborating the results of the 2019 World Athletics Championships and Marathon Majors allows for closer analysis.

Across both men and women, the results of the 6 majors and World Championships read: 14 races, 12 wins in Nike VF technology. Most impressive of those wins was the fastest marathon ever run by a woman as Brigid Kosgei ran 2:14:04 to break the World Record in Chicago by 81 seconds, a time that had stood for 16 years. Meanwhile, just two weeks earlier Keninisa Bekele had shocked the running-world at Berlin – winning in 2:01:39. Bekele’s time that day remains the second fastest marathon ever run and is only 2 seconds behind Kipchoge’s World Record set on the same course a year earlier.

MORE THAN MARGINAL

When the first round of lab-tests on the VaporFly were released, the results showed a 3-4% decrease in oxygen cost transportation (COT), which translated into an estimated 2.0-2.5% performance benefit for an elite marathon runner. Then, in July of 2018 the New York Times published data suggesting that runners in the VaporFly were more than 1.0% faster than those in the next-fastest racing shoe. 18 months later the Times increased that estimated benefit to between 2-3%.

In comparison, throughout the 1993 season Alain Prost qualified fastest in 13 of 16 races, finishing on the podium in all but 1 that he started from pole. In 4 of the first 5 races his time in qualifying was an average of 2.3% faster than the next car that wasn’t his teammates’ FW15c. By the end of the season, even as rival teams were refining their own active suspension, Prost’s average qualifying speed over rival teams was 1.4%.

Like the effect of Nike’s VaporFly technology, the dominance of the FW15c was astounding. In the 3 years preceding 1993 and the season following (1994), the winning constructor in F1 had averaged 27% more points than the second-placed team. Even Mercedes, who have dominated the modern era of the sport have an average points difference of 28% over 2nd place since 2015. Yet in 1993 Williams had finished the season with 50% more points than their nearest rival – the McLaren team featuring the greatest driver of all-time, Artyon Senna.

ACTION AND REACTION

In response to the FW15c the FIA updated the rules and banned Active Suspension (along with several other electronic aids) for the 1994 season. Their reasoning was essentially twofold: Safety and cost.

Regulators had become concerned with what they perceived to be a dangerous increase in cornering speed, while fearing an expensive development race that not all teams could afford. There was also widespread criticism that the cars were becoming too easy to drive, reducing the influence of driver skill and diminishing the sports appeal to fans as genuine racing.

Earlier this year World Athletics reviewed its own rules in response to the impending release of the latest generation of VaporFly technology; the Nike AlphaFly NEXT%. An internal work group was established to investigate, with many in the sport expecting the shoe would be considered ineligible for official competition given its infamous stack height.

World Athletics responded by amending their Technical Rules, and in doing so determined a sole thickness limit of 40mm. This new established threshold was to the exact specification of the AlphaFly – which Nike released a week later.

Exceeding track limits and cornering speed is obviously not a consideration for World Athletics. However, as was the case in F1, there is growing concern for the integrity of performances and the declining significance of the athlete. This sentiment is perhaps best summed up by sport scientist Ross Tucker:

“When the range of responses to the equipment are larger than the difference between athletes, the integrity of the result is diminished”.

DOLLARS AND SENSE

In the 1990’s car companies were coming back to F1 because of its high-tech profile, and with that investment came increased innovation. But as the cars were getting ‘cleverer’, the drivers were playing a considerably smaller part in the outcome of the race, which Motor Racing Commentator Simon Taylor described as “not good box office”.

The fate of the FW15c is a symbol that even in F1, a sport that many see as a technological and financial free-for-all, there are limits. There is such a thing as too fast and too much technology; there is a formula.

This struggle is the situation that athletics now finds itself in. The [re]introduction of carbon-plate technology has resulted in considerable investment by almost every major shoe manufacturer, which in turn has helped to revive the profile of the sport. Yet the question remains – have shoes made the sport unrecognisable, or is this simply a new landscape?

It seems that running now has an entirely new formula.