If I’m recalling my year 12 physics correctly – which may be a risky proposition – two equal waves meeting as they cross a pond will cancel each other out at one point and perfectly reinforce each other at some other point.

If I’m recalling my year 12 physics correctly – which may be a risky proposition – two equal waves meeting as they cross a pond will cancel each other out at one point and perfectly reinforce each other at some other point.

The first phenomenon produces a flat point as the upward displacement is exactly equal to the downward; the second produces a point at which the displacement is precisely double the amplitude of either wave.

Such a point was reached on Easter Monday as two of the running world’s most venerable events occurred. I speak of the Stawell Gift and the Boston Marathon each of them around seemingly forever and which, due to the vagaries of the lunar cycles and the Gregorian calendar – the two waves in this analogy – intersected on Easter Monday, 2022. International time differences imposed a flat point, but the two events created a high to close the Easter long weekend.

It’s a rare co-incidence. Neither event is held on a fixed date. Boston is held on a fixed day, Patriots Day, celebrated on the third Monday in April. That tethers the race from Hopkinton to downtown Boston to somewhere between 15 and 21 of the month. Stawell is always Easter Monday, but that can be any time from late March to late April as Easter is celebrated on the first Sunday following the first full moon after the 21 March autumn equinox.

View this post on Instagram

The Gift is slightly the older of the two. It was first run in 1878, Boston in 1897, the year after the first Olympic Games of the modern era were celebrated in Athens. Stawell continued all the way through World War I but was not contested from 1942 to 1945, inclusive, during World War II.

Boston was run throughout the WW II years, but was suspended in 1918, when an Ekiden-relay style race was contested between teams representing various US army camps. In his history of the Boston Marathon, Tom Dederian concluded the event “proved to be neither good athletics nor good public relations,” but that’s another matter.

Neither event was cancelled for the (so-called) Spanish flu epidemic following the first World War but Covid-19 saw both Stawell and Boston cancelled in 2020. Stawell was held on its usual date in 2021, Boston postponed until October: 2022 has seen normal service resumed.

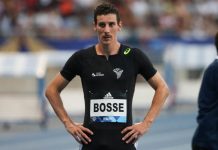

For those who did not travel to Stawell for this year’s Gift meeting, there was the opportunity to take it in on the Seven Network. Dave Culbert and Tamsyn Manou provided the commentary, Jason Richardson was the anchor man and on-ground interviewer. The doyen of Olympic coverage, Bruce McAvaney, made a cameo appearance.

Whether or not Stawell is your cup of tea, it was great entertainment. Culbert, Manou and Richardson (the latter pair both previous Gift winners) are knowledgeable and bounce ideas and topics around between themselves as effortlessly as the Harlem Globetrotters share the basketball. McAvaney added the context, providing perhaps a hint of self-deprecation with the obligatory statistic that only eight men had won the Gift off a handicap shorter than five metres in discussing the chances of scratch-marker Eddie Nketia.

Inevitably, Nketia did not make it nine, though he did run superbly to take fourth place in 12.27 seconds. For what it’s worth – less than the winner’s $40,000, that’s for sure – Nketia’s time was almost a full tenth of a second faster than Josh Ross (12.36) ran in winning the 2005 Gift off scratch and virtually the equivalent of the hand-timed 12.0 Jean-Louis Ravelomanantsoa did in winning off scratch in 1975.

The 2022 race was a handicapper’s nightmare. We’re more-or-less accustomed to the men’s Gift winner getting in with a handicap several metres better than his true form would merit. Like it or not, that’s par for the course. But this year the first three athletes would have won the Gift by at least a metre.

Harrison Kerr, of 9.25 metres, beat Hamish Lindstrom (7.75) by a metre-and-a-half, 11.85 to 12.01. Lindstrom in turn had a metre to spare over Jesse McKenna (12.17 off 6.25) with another metre to Nketia in fourth. To put that another way, no Kerr means Lindstrom would have won easily. And without Kerr and Lindstrom, McKenna would still have won comfortably.

The result doesn’t sit well with a handicap system that is supposed to have all six finalists in with a chance of winning. This ideal situation rarely occurs, to be fair, though it did in the women’s Gift when the six runners were separated by less than the gap between first and second in the men’s final, the backmarker (off 0.75) finishing just 0.02 behind the winner.

Carla Bull, off six metres, held her nerve and her form brilliantly in winning by a hundredth of a second – 13.78 to 13.79 – from Clare De Salis (8.5). Mia Gross, fourth in the national 100 finals, was third off 0.75 in 13.80. The other three finalists – Cassandra Wang-Lecouter (8), Lucy Carter (5) and Danielle Shaw (6) ran 13.84, 13.85 and 13.89, respectively.

View this post on Instagram

The other point which needs a little context is the statistic that Harrison Kerr ran the fastest winning time in 27 years since Glenn Crawford’s 11.79 in 1995. That’s true as far as it goes, but it doesn’t mean Kerr was even the fastest runner in the final. Using a rough calculation of 10 metres per second speed, Nketia was way faster, while Lindstrom and McKenna would have finished within hundredths of the winner.

As ever, the art of winning a handicap race is to hold your nerve and form all the way to the finish line, so that on the day, off your mark, you are the best.

Hamish Kerr did that brilliantly, looking as smooth and relaxed as if he was running a training wind sprint. That was his triumph at Stawell and well done to him for that.

Different time zones meant Boston, Patriots Day, 2022 did not clash with Stawell, Easter Monday. But the two races were similar.

The women’s race was closer and much more exciting than the men’s, for one thing. In a final duel evocative of Sammy Wanjiru and Tsegaye Kebede in Chicago in 2010, Peres Jepchirchir and Ababale Yeshaneh exchanged the lead seven times in the final kilometre before Jepchirchir won, 2:21:02 to 2:21:08.

View this post on Instagram

The men’s race seemed destined for a similar finish until Evans Chebet unleashed a 13:55-split from 35 to 40km to burst clear. He won in 2:06:51 from fellow-Kenyan and Olympic fourth placegetter Laurence Cherono’s 2:07:21. Fifteen runners had been in the lead pack as late as the top of Heartbreak Hill (around 35km).

Those times don’t seem that fast at first glance. LetsRun, however, noted that Chebet’s was the eighth-fastest run in Boston history (Geoffrey Mutai’s 2:03:02 in 2010 is fastest) and that six of the seven times ahead of Chebet (my emphasis) came in the wind-aided 2011 race, implying 2022 was not aided.

Chebet’s was also the third-fastest winning time, behind Mutai and Robert Cheruiyot (2:05:52 in 2010).

Similarly, Jepchirchir’s time is the third-fastest winning performance in Boston, behind Bizunesh Diba’s course record 2:19:59 in 2014 (Rita Jeptoo, first woman across the line in 2:18:57, was subsequently DQ-ed for drug use). Second-fastest is the 2:20:43 by Margaret Okayo in 2002.

‘Record ineligible’ it may be, but times almost any year tell us Boston almost any year is not an ‘aided’ course.