Written by Lachlan Chisholm, Physiotherapist

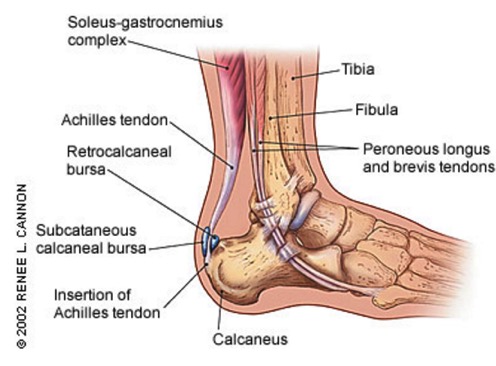

The Achilles tendon is a very common injury area in running and sport in general. Injury to the Achilles has a multitude of potential causes. The most common site of injury is an Achilles tendinopathy to the mid portion of the tendon, the other common site is the insertion to the heel. There are also other pain causing structures around the Achilles including the retrocalcaneal bursa and subcutaneous calcaneal bursa.

The way we treat tendons has changed over the last few years and will continue to evolve as our understanding of tendon injuries continues to improve. From my experience, each tendon injury responds slightly differently so it is hard to give specifics in this kind of forum. So I will focus mostly on general injury prevention advice and general advice in regards to the current methods of Achilles rehabilitation.

The Achilles connects the calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus and plantaris) to the Calcaneus (heel bone) and allows you to plantarflex, or point your foot/ankle. The Achilles is the thickest and strongest tendon in the body, and the tendon can receive a load stress 7.7 times body weight when running, in my case of a 75kg middle distance runner that is up to 577 kg per step! However, if that force is not applied in a longitudinal manner, say a lateral force is applied, it becomes weak and very susceptible to injury. So, as you can imagine the Achilles takes a lot of the load which also makes it susceptible to injury if it is overloaded or loaded in the wrong way.

Prevention

The best way to treat an Achilles injury is to prevent it in the first place, so my main tips for prevention of Achilles injuries are;

- Adequate strength and flexibility– As a general rule I expect all of my running patients to be able to do 30 (slowly 1sec up 1sec down with good control and alignment) single leg heel raises. I also aim for a minimum of 12cm knee to wall (have your toe 12cm from a wall and keeping your heel on the ground lunge your knee forward to touch the wall).

- No compressive loads– This means you cannot have anything pressing into your Achilles. Sometimes the back of a shoe, for example, can press into your Achilles and this changes the line of force through the Achilles causing an inappropriate load, leading to Achilles tendonitis.

- No sudden changes in load– By this, I mean no rapid increases in training volume, type or surfaces, and type of shoes. When it comes time to move through phases of training this must be done gradually over a period of weeks to allow the body to adapt to the new load whether it be increased volume or increased intensity of training. The same applies for training surfaces and your change from normal training shoes to flats and spikes. (The lower heel in your spikes means your ankle range of motion (ROM) increases when you run which increases the time and ROM your Achilles is under load. This also includes getting adequate rest/recovery between sessions.

- Appropriate footwear- This one can be a tricky subject with the minimalist/maximalist debate. Basically, you need a shoe that fits your foot type and fits comfortably and that is not worn out. I generally find I get between 500-700km out of a pair of shoes before they feel “dead” and are showing significant crush signs on the cushioning.

Injury Rehabilitation

If you are unlucky enough to develop Achilles pain you really should see a physiotherapist or other appropriate health care professional as soon as you can. But in terms of general advice, this is what I give my patients.

Often the first signs of an Achilles tendinopathy is your first step or two out of bed in the morning, the back of your heel feels stiff and sore but after a few steps/minutes the pain goes away and you think no more of it. This is the best time to get onto it and get proactive about treating it. Basically a bit of ice, gentle stretching, self-massage/foam rolling, and a little bit of relative rest (reduced load). You can also make a start on controlled loading i.e. heel raises/strength.

But once you have passed that point you will notice it when you start to run but again it “warms up” so you continue to train as normal. At this stage, I am not against continuing to train through an Achilles injury as long as it is carefully monitored and managed and is improving with the right treatment and management. However, it tends to improve faster in my experience with modified training or cross training.

You should monitor your morning pain and use this as a guide as to how your Achilles is progressing. Monitor how bad out of 10 the pain is with your first few steps in the morning and how long it takes to go away? If it is getting worse you are doing too much and need to reduce the load.

As above, you want to ice and self-massage and some gentle stretching (if part of your problem is reduced range of motion). Then you need to start loading your tendon in a safe and controlled manner. Tendon healing responds to load, if it is loaded correctly, you can end up with a strong pain-free tendon at the end of your rehabilitation. If not you often end up with a stiff sore tendon and long term problems.

At this point you start out with a period of isometric loading in a neutral ankle position (i.e. not up on your tippy toes and not hanging your heel off a step. Your heel should be held just off the ground or a step – but held at the step height) for 45sec x 3 x 2 daily. Do this on one leg at a time and repeat on the other leg. I use 4/10 as a guide on pain if you are getting over 4/10 pain start by doing both legs at the same time. You will often find that after doing this you have a short pain-free or reduced pain period. It also seems to improve muscle activation. After a week or so you modify this by adding a set of heel raises in between each isometric hold. The number depends on your strength but I often start with 8-10 and progress to 15. As you improve you then reduce the isometric loading to be used as a pain management/ warm up tool and then progressively increase the number of heel raises until reaching 30 single leg heel raises.

You should continue to perform these exercises for up to 12 months once pain-free, as tendon repair and remodelling continue long after your pain has ceased.

Written by Lachlan Chisholm, Physiotherapist

About Lachlan Chisholm

Lachlan was one of Australia’s leading 1500m runners for many years. His 1500m PB is 3:37 and he is a two-time Australian 1500m champion.

Lachlan currently works at Nowra Physiotherapy and Sports Injury Clinic

Comments are closed.