MATT FITZGERALD – Runner’s Tribe

Matt Fitzgerald is an acclaimed endurance sports coach, nutritionist, and author. His many books include The Endurance Diet, 80/20 Running, and How Bad Do You Want It?

Among the benefits of travelling internationally is that it gives you a different perspective on your own country. For example, in 2015 I spent two weeks in Kenya conducting research for my book The Endurance Diet, and it was there that I came to fully appreciate how screwed up America’s relationship with food is.

As part of my research, I ate nothing but traditional Kenyan food at every meal, and I returned to the States two pounds later than I’d been when I left. The most fattening characteristic of any diet is how processed its constituent foods are, and the Kenyan diet is minimally processed. But that’s not the only reason I lost weight during my East African sojourn. The other reason is that there are no food commercials on Kenyan television. None. Not that I actually watched a lot of television while I was there, but the larger point is that food is not constantly shoved in people’s faces in Kenya as it is here. And it has an effect. By the end of my stay, I found myself thinking about food a lot less than I did back home.

I thought of this experience recently when, against my better judgment, I waded into an online debate about fasted workouts. My goal in doing so was to help the other parties recognize fasted workouts as the simple, straightforward practice they are, but this proved impossible, and I think it’s because America has a screwed-up relationship with food.

I was up against two separate factions in this debate, both of which viewed fasted workouts as extreme and radical, each in a different way. One faction regarded the practice of completing a workout on an empty stomach as a kind of torture—a gratuitous sufferfest ending in degrees of exhaustion never approached in regular workouts. This is absurd. A fit and well-nourished athlete who chooses to delay breakfast until after a workout is only minimally compromised by having their metabolic fuel tanks less than fully topped up. The science is rather abundant in this area. For example, in a 2012 study by Australian researchers, trained cyclists completed 60-minute time trials in fasted and non-fasted conditions, averaging 282 watts after a good breakfast and 273 watts on empty stomachs. That’s a 2.8 percent difference in performance.

In prolonged exercise bouts, the impact of skipping breakfast is greater but still far milder than some athletes seem to believe. A 1999 study by Tim Noakes and colleagues found that moderately trained subjects lasted an average of 136 minutes in a time-to-exhaustion cycling test at 70 percent of VO2max in the fed state compared to 109 minutes in the fasted state. That’s an 18 percent difference. In practical terms, this means you should feel no more fatigued at the end of a 14-mile fasted training run than you would be at the end of a 16.5-mile post-breakfast run. If you factor in the additional effect of withholding calories during the run, which fasted workouts require, the difference becomes somewhat greater, but even then it’s nowhere close to extreme.

Why, then, do some athletes regard fasted workouts as extreme? I think it’s because we are overfed as a society. In America, unlike Kenya, not only are our television screens filled with (junk) food advertisements, but these advertisements are carefully designed to brainwash us into being disposed to overeat, attaching positive associations to words like “crave” and “stuffed” and negative associations to “hunger” (and I’m talking about normal appetite, not chronic malnourishment). Consider Snickers’ “You’re not you when you’re hungry” ad campaign, which encourages viewers to keep a 2-ounce calorie bomb in their pocket wherever they go so they can cram it down their gullet the moment they feel the slightest hint of want in their tummies. We all like to think we’re immune to such mind-meddling, and we’re all wrong, and the fact that a certain faction of athletes finds it unimaginable to occasionally delay breakfast until after they’ve completed a workout proves it.

Another thing that Kenya has a lot less of than America does is disordered eating. Not all pockets of American society have high rates of eating disorders, but endurance sport is one pocket that does. Research has shown that people who struggle with disordered eating tend to have a history of trying popular diets (e.g., keto) and dietary practices (e.g., intermittent fasting). This is not to say that such diets and practices cause eating disorders; rather, it’s evidence that individuals who are predisposed to disordered eating tend to be attracted by such things.

Fasted workouts fit this mold. They are the type of practice that certain athletes are drawn to for the wrong reasons. Although I don’t know of any real cases, I can easily imagine that some athletes have overused or misused fasted workouts and subsequently developed eating disorders. Because this risk exists, a certain faction within the endurance sports community believes that fasted workouts should not be promoted. But to me this is like banning automobiles because some people drive while impaired. Depriving all athletes of the opportunity to benefit from this practice is unfair to the majority of athletes who are at low risk of developing an eating disorder and it is also not a legitimate solution to the problem of disordered eating within the athletic community.

As an endurance coach and writer, I’m focused on promoting fasted workouts responsibly. Although not inherently risky, fasted workouts are an advanced method that only makes sense for athletes who are already doing the basic things that yield bigger improvements in fitness, which include training at high volume, maintaining high diet quality, obeying the 80/20 rule of intensity balance, and eating enough throughout the day every day. Fasted workouts are meant to help athletes who’ve already realized 99 percent of their genetic potential through these and other fundamentals squeeze out that last 1 percent. For everyone else—including all youth athletes—they can wait, and for those who have any kind of history of disordered eating or any reason to believe they might be at risk for it, they can wait forever.

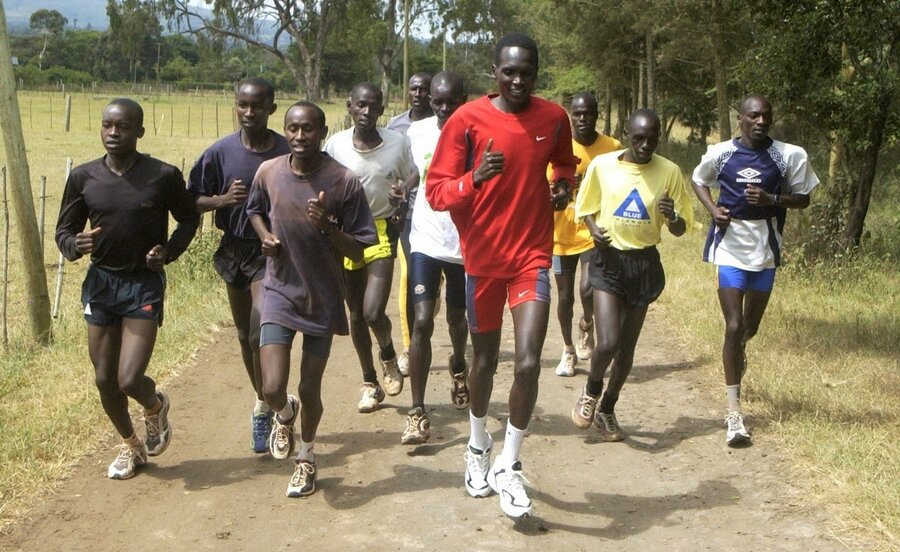

By way of closing, I would just like to mention that in Kenya, for cultural rather than scientific reasons, most runners do their first and hardest run of the day before breakfast every single day. Someone needs to tell them how radical and extreme this practice is so they can stop doing it and finally get good at running!