A column by Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

When Nike announced recently that its ‘window’ for the attempt to run the first sub-two hour marathon was 5-7 May, an intriguing possibility was raised.

The date dead-centre in the window, 6 May, is the sixty-third anniversary of the breaking of another famous barrier in athletics. On that day in 1954, Roger Bannister became the first man to break four minutes for the mile.

Not surprisingly, given that almost everything about the Breaking2 project is commercially driven, the possibility of sub-2 being achieved on the same day as sub-4 drew favourable comment. Almost assuredly, the choice of dates was a creative coincidence.

The aim of Breaking2 is not necessarily to break two hours, Nike assures us, nor even to break the world record currently held by Dennis Kimetto at 2:02:57. Rather, “we just want to show it can be done. We want to show that it’s within the capability of human physiology,” according to the shoe company’s vice-president for footwear innovation (now there’s another coincidence!).

Regardless of the avowed aims, however, should one of Olympic champion Eliud Kipchoge, silver medallist Lelisa Desisa and world record holder for the half-marathon Zersenay Tadese, run anything quicker than Kimetto, people will be falling over themselves to acclaim the performance as a “world record”.

Which raises one more intriguing possibility: after 63 years, could one of the most contrived records in athletics history be commemorated by another, equally contrived, performance.

The similarities abound. At the most basic level, both projects – the sub-4 minute mile and the sub-2 hour marathon – are proceeding on the basis that the goal cannot be achieved through the efforts of one athlete alone, no matter how gifted. A team effort is required.

Bannister was paced for almost three-and-a-half laps of his historic 3:59.4 at Oxford’s Iffley Road track on 6 May, 1954. The assistance was provided by his two friends and training mates Chris Brasher and Chris Chataway. Brasher busted a gut to lead for two-and-half-laps; Chataway took over and led almost to the final 220 yards.

Kipchoge, Desisa and Tadese will most likely have some pacing assistance – a test half-marathon on the Monza motor circuit in Italy that will be used for the attempt showed a phalanx of pacemakers behind a pace/timing vehicle. More importantly, Nike will seek to control as many of the other variables that influence marathon performance as they can.

On the all-important matter of weather conditions, Runner’s World reports Nike’s weather modeling suggests that, within any three-day window in early May, they should have a roughly 90 percent chance of getting at least one perfect day.

Then there is footwear which reportedly utilises a system of energy storage and return similar to the ‘blades’ worn in AWD competition.

Why, there’s even a ‘window’ involved in both attempts. The marathon has its three-day window, during which at least one perfect day is virtually ‘guaranteed’ (these blokes could go broke very quickly playing two-up).

A window, or windows, also featured prominently in Bannister’s mile. There was the train window he gazed out of as he travelled to Oxford with Franz Stampfl. Outside, the wind whipped through the branches of the trees. Then there was the window seat through which the sun was shining when he called in on Chataway before the race. “The day could be a lot worse,” his friend observed.

Finally, there was the dressing-room window at Iffley Rd through which Bannister, Brasher and Chataway watched the flag of St George on the nearby church. The flag, standing out from the flagpole most of the afternoon, flopped down as the weather calmed just before the start of the race.

Bannister’s performance is rightly remembered as one of the greatest moments in athletics history. A mystique had built up around the four-minute mile and however much it can be rationalised this was not totally justified (the hiatus either side of WW II was undoubtedly a factor, for instance), the breaching of the “barrier” resonated around the world. It still does: the four-minute mile was voted the greatest sporting achievement of the 20th Century in one millennium poll.

But it was highly contrived. Although the pacing arrangements do not appear ‘miles away’, so to speak, from modern practice, they were highly unusual then. A year earlier, Bannister had been denied a British record for a race paced, initially, by Australian Helsinki Olympic finalist Don Macmillan and then by Brasher, who had jogged until Bannister was about to lap him and then taken over the pacing role. That was too artificial, hence the modified plan for the Oxford race.

More importantly, such pacing help was not available to Bannister’s main rivals, John Landy and Wes Santee. At best, they were helped by enthusiastic club or university mates whose abilities did not stretch beyond two laps and, indeed, rarely as far as that.

If a sub-2 hour, or even a ‘world record’, is achieved on 5, 6 or7 May at Monza, it, too, will be a tremendous achievement. No doubt, we will still be talking about it for years to come.

But just as Bannister’s great competitive achievements in 1954 came in beating Landy at the Empire Games in Vancouver and winning the European championships, the greatest marathon moments come in racing the clock and the opposition when there is no-one else there to help you.

End

Video: Bannister’s Sub 4 (1954)

About the Author-

Len Johnson wrote for The Melbourne Age as an athletics writer for over 20 years, covering five Olympics, 10 world championships, and five Commonwealth Games.

Len Johnson wrote for The Melbourne Age as an athletics writer for over 20 years, covering five Olympics, 10 world championships, and five Commonwealth Games.

He has been the long-time lead columnist on RT and is one of the world’s most respected athletic writers.

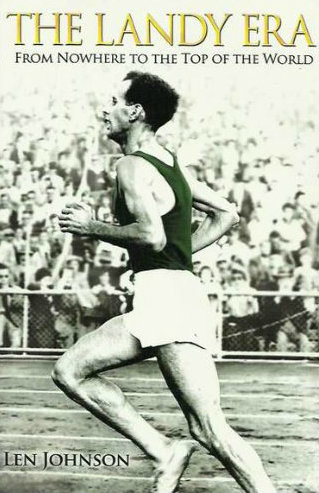

He is also a former national class distance runner (2.19.32 marathon) and trained with Chris Wardlaw and Robert de Castella among other running legends. He is the author of The Landy Era.